What are uterine fibroids?

The cause of fibroids is not entirely known to those in the medical field. Research and clinical observations have found associated links that include changes in genes which can differ from the normal cells of the uterine muscle, hormonal influences (fibroids typically contain more oestrogen and progesterone receptors) and other factors, such as substances in the body that may affect growth of fibroids.

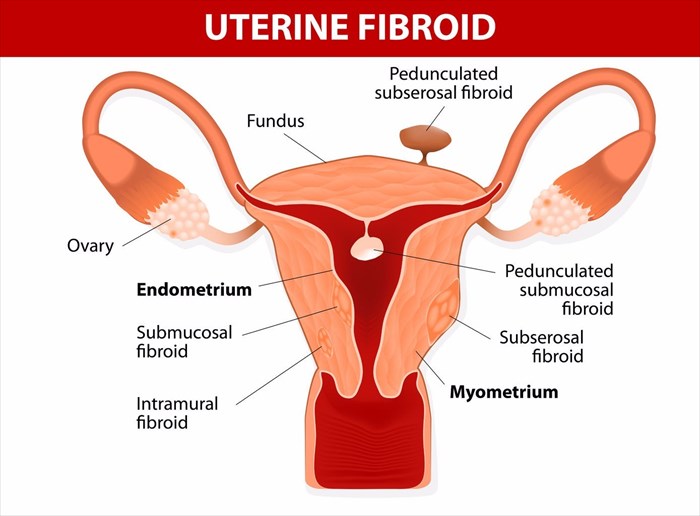

Most believe that uterine fibroids originate from a stem cell in the myometrium (the muscular tissue in the uterus). The cell then divides multiple times and eventually creates a rubbery mass that is firmer than the nearby tissue.

There are different types of uterine fibroids – intramural fibroids (these develop within the muscular uterine wall), submucosal fibroids (these develop as bulges into the cavity of the uterus) and subserosal fibroids (these develop on the outside of the uterus).

Uterine fibroids may develop gradually or quickly. They may also develop to a specific size and remain that way. Some go through ‘growth spurts’ while others shrink without much intervention.

There are various options for treatment which doctors can recommend to a woman with fibroids, especially if she is experiencing symptoms or intends to try and fall pregnant. Options range from non-invasive, to minimally invasive and traditional surgical procedures which all either target fibroid tissue or aim to remove them altogether. In some instances, procedures cannot bypass the uterus and the removal of fibroids may include a woman’s womb too.

Uterine fibroids and pregnancy

Uterine fibroids aren’t necessarily preventative of a woman’s ability to conceive. Submucosal fibroids are known to cause complications of infertility and pregnancy loss, however. Any type of fibroid can also interfere with pregnancy and increase the risk of complications. These can include foetal growth restrictions, placental abruption or even preterm delivery of a baby.

In some instances, uterine fibroids can shrink (or even disappear) after pregnancy when the uterus returns to its normal size.

To date, treatment options which are best opted for if a woman wishes to have children of her own include:

- Non-invasive: MRI-guided focused ultrasound surgery (FUS)

- Minimally invasive: Uterine artery embolisation, myolysis, laparoscopic or robotic myomectomy, or hysteroscopic myomectomy.

- Surgery: Abdominal myomectomy.

Normally, a doctor will assess a woman’s desire to have her own children during a complete fertility evaluation. If pregnancy is something a woman would like to try for, treatment via an endometrial ablation or hysterectomy are immediately ruled out. Both treatment options interfere with the normal function of the uterus.

A hysterectomy involves the removal of the uterus, which is effective in preventing any further development of fibroids in the future. It also prevents any possibility of pregnancy for a woman. An endometrial ablation involves the use of heat, microwave energy, electric current or hot water to destroy the interior lining of the uterus. The effect results in reducing a woman’s menstrual flow or ending the ability to menstruate altogether. The chances of fibroids developing in the future are slim to none (fibroids can, however, still develop on the outside lining of the uterus), and likewise, the possibility of pregnancy.

Myomectomy procedures (surgery to remove uterine fibroids) are more often than not, the treatment option of choice when it comes to preserving a woman’s ability to fall pregnant. There is a risk of a necessary hysterectomy even after a myomectomy procedure.

How will the new study positively influence women with uterine fibroids?

Uterine fibroid embolisation (UFE) is a minimally invasive treatment procedure that a new study, published on 13 June 2017 in the journal Radiology, has found may not only be helpful in helping women with fibroids conceive successfully, but most importantly, also help to prevent complications with future fertility.

UFE, also known as uterine artery embolisation, is a radiological procedure that has been found to effectively block the flow of blood to fibroids. This reduces fibroid growth and can reduce their size considerably. Initially this technique was thought to also potentially block blood flow to the uterus entirely, and thus would not be useful in helping women to conceive. However, findings have proved that this is not the case.

It has been estimated through previous clinical studies that one in every four women suffering from fibroids will experience problems with fertility or having successful pregnancies. Treatment is normally invasive (in varying degrees) with the standard recommendation being a laparoscopic, robotic or hysteroscopic myomectomy procedures (removal of fibroids via surgery while leaving the uterus in place). A UFE is considerably less invasive and a simpler procedure to perform too.

Dr Joao Pisco, the director of interventional radiology at Saint Louis Hospital (Libson, Portugal) is the author of the new study that looked specifically at the effect of UFE on fertility (the likelihood of a successful pregnancy and live birth following this treatment procedure).

Taking into consideration past concerns that the procedure would restrict blood flow to the uterus, a partial UFE was tested. This blocks only the tiny arterial branches, and does not totally restrict blood flow to uterine fibroids. The corresponding larger blood vessels are virtually unaffected with a partial UFE. The partial procedure also allows some blood flow to the uterus, arteries and ovaries (effectively reducing potential risks normally associated with a conventional UFE). This in effect increases the rate of potential pregnancy and lowers possible complications or issues.

The findings of partial UFEs were also compared to those of conventional UFEs. Fibroid shrinkage rates were similar in both groups. Partial UFEs, however, experienced lower complication rates, high pregnancy rates (with the birth of healthy new-borns) and fewer obstetric problems during pregnancy.

So, how does the procedure work?

Small gel particles are injected into a fibroid through blood vessels. The gel then foams up and blocks the flow of blood to the tip of that particular blood vessel. This effectively prevents the fibroid from growing and stimulates shrinkage instead.

Initially the use of gel for this procedure was thought to be risky. The fear was that the gel may reach part of the uterus (the endometrium or lining of the uterus) and the ovaries, and thus if a woman did fall pregnant, blood flow may be restricted from a growing foetus. The study went ahead anyway, and indicates that perhaps this fear was a little misguided.

The new study assessed 359 women who were unable to fall pregnant naturally as a result of their fibroids. The study involved about 6 years of assessments to follow-up on progress or potential problems. Of the 359 women, 149 women who underwent either a UFE or partial UFE procedure achieved a successful pregnancy (one or more times) in the period of assessment. Of these, 131 women successfully delivered a total of 150 healthy babies.

The study found that of the women who experienced successful pregnancies and live births, 85% were first time experiences. The clinical success rate of participating women was approximately 79% for symptoms related to fibroids. About 14.6% of the partial UFE group experienced complications, and 23.1% in the conventional UFE group.

UFE procedures were repeated in 28 women who experienced complications where it was found that the initial treatment wasn’t entirely successful. Of these women, 11 went on to achieve successful pregnancies.

With either procedure, it has been found that pregnancy is a possibility, as well as the successful birth of healthy babies. The study thus proves that UFE may become the primary treatment option instead of myomectomy procedures going forward.

Women with large fibroids or multiples may now comfortably indulge in a little hope. Often, the recurrence rate of fibroids for many women stands as high as 60%. With UFE procedures having proved such rates of success in the new study, there is certainly reason to have hope.

The study also noted that UFE procedures can be performed in women who have had a prior myomectomy procedure or fertility treatment, such as IVF (in vitro fertilisation).

As with any medical procedure, UFE does carry some risk and strict guidelines. Women who opt to have a UFE procedure will need to factor in a waiting period of at least 6 months after having the treatment before trying to conceive. Fibroid shrinkage is not an instant process and will take time to heal after the gel foam injection.

If a woman does try and conceive during the ‘waiting period’, she still runs the risk of a miscarriage or further infertility complications. If a pregnancy is successful, even during the healing period, she runs the risk of a preterm contractions, preterm delivery of the baby or the placenta being implanted in the incorrect location in the body.

The findings conclude that UFE as fibroid treatment is a possible fertility-restoring procedure for women with uterine fibroids and can result in a normal pregnancy with the very same complication rates as those able to conceive and carry naturally, despite falling into a high-risk category.

"Because of this study, I feel more reassured that women who have undergone UFE can use fertility medication or receive IVF [in vitro fertilisation] and have a good perinatal outcome," says Dr Tomer Singer, director of reproductive endocrinology and infertility at Lenox Hill Hospital in New York City.

Researchers involved in this study continue to work with participants even after the publishing of their most recent findings. UFE treatments are continuing and data is still being compiled. The team has also announced 12 additional pregnancies achieved since the time of writing the report. In addition, more live births have also been achieved, bringing the total of healthy babies delivered to 200 in the time between writing and publishing the report.

Researchers now aim to compare their overall results of partial and conventional UFE successes even further, as the study continues.