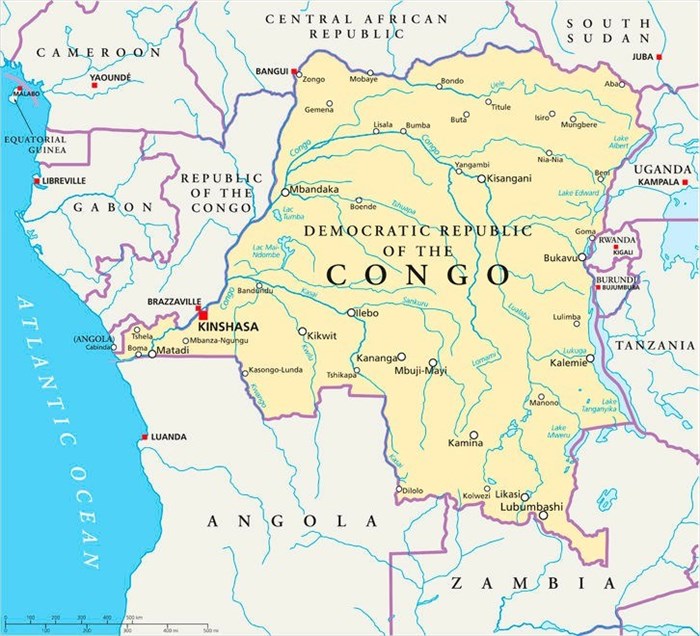

Since the official outbreak announcement by the WHO (World Health Organisation) earlier this month, many of the suspected cases, mostly identified in the Bikoro health zone, a market town close to Lake Tumba, and over 100km from the capital of Equateur Province, Mbandaka, have resulted in fatalities.

Rapid response efforts are already underway and all participating authorities including WHO Director-General Dr Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, who recently visited the country, are doing all they can to ensure that the immediate crisis is contained and that those affected are provided with sufficient and effective medical care.

Eight other Ebola virus outbreaks have occurred in the DRC over the course of the past 40 years. Prior to the current outbreak (identified to be caused by the Zaire ebolavirus species), the last occurred in the Likati health zone in the Bas-Uele province, north of the country, last May (2017).

For the province of Equateur, this is the fourth outbreak, with the other incidences taking place in 1976, 1977 and 2014. The Bikoro health zone itself has not specifically experienced an outbreak, until now. The population of the town is estimated at over 163 000. The Equateur province has an estimated population of 2.5 million and around 284 registered health facilities. In Bikoro, there are 3 hospitals and 19 other health centres facilitating healthcare to the town. The functionality of these hospitals and healthcare centres, however, is limited and relies on international organisations to help maintain regular stock supplies.

Initially, reported outbreak cases were only identified in the more remote locations of the DRC but now one other has also been reported in Mbandaka. How far reaching actual infections may be in the country as a whole has not been entirely determined. On-the-ground teams are actively investigating this so as to gain a clearer sense of the extent of the confirmed outbreak, as well as to assess the risk of the disease spreading.

One concern with regard to the spread of this disease is the proximity of Bikoro health zone to the Congo River which places the Republic of the Congo and CAR (Central African Republic), as well as other neighbouring countries at risk of outbreaks. Neighbouring countries have been notified to remain alert.

Currently the WHO regards the DRC, as a nation, as most at risk, even though reported cases appear to be geographically limited. The nature of the disease and its transmission capability, as well as a lack of information at this stage regarding the extent of its spread necessitates the high-risk consideration. Other neighbouring regions are currently considered as being at moderate risk, and the international public at large at low risk (since no further cases have been reported outside of the affected towns at this stage). As such, no warnings are currently in place restricting travel and trade to the country.

What is Ebola virus disease (EVD)?

The disease was first identified in 1976 in the village of Yambuku near the Ebola River in the DRC, as well as in a remote area of Sudan, the two outbreaks, and all subsequent occurrences have had a devastating effect on those who contracted it.

The exact origin of the Ebola virus is not specifically known. However, it is thought that this acute infectious disease first emerged from an animal source – possibly hosted by fruit bats (Pteropodidae) who live in the area. Other non-human primates, like chimpanzees, monkeys and gorillas, are also known to be vulnerable to infection.

Infection is believed to be caused by one of five virus species. Four Ebola virus species are known to have infected human beings:

- Zaire ebolavirus (Ebola virus)

- Sudan ebolavirus (Sudan virus)

- Taï Forest ebolavirus, formerly known as Côte d’Ivoire ebolavirus (Taï Forest virus)

- Bundibugyo ebolavirus (Bundibugyo virus)

The Reston ebolavirus (Reston virus) has been identified as a disease-causing infection in non-human primates and pigs. (2)

Contact with the infected animal, carrying any species known to affect humans, is believed to be the mechanism for transmitting the virus between animal and human beings. Humans subsequently spread the virus among themselves. Contact with infected animals occurs during the butchering, cooking and eating processes. Transmission between humans is more typical through contact with bodily fluids – secretions like urine, saliva and semen, or even blood contact which enters the human body via the mucous membranes (nose, mouth or eyes) or broken skin. The virus can also be transmitted via sexual contact between human beings. Infected bodily fluids or even objects and surfaces (including clothing and bed linens) contaminated by these can transmit the disease if contact is made with them.

Symptoms include severe headache, fever, fatigue, muscle pain, body weakness, vomiting, abdominal pain, diarrhoea, rash, bleeding (internal and external) or bruising that cannot be explained. Impaired function of the liver and kidneys can also develop. Once a person is exposed to the virus, symptoms begin to display within 2 and 21 days (most typically becoming noticeable within 8 to 10 days).

Once an infection is active within a community, everyone within a close range is highly vulnerable, especially family members, healthcare workers and anyone who has direct contact with an individual who has died from an infection (this included anyone handling the body during burial rituals) as levels of the virus remain high even after a person has died and can still be transmitted through contact.

What is the outbreak situation in the DRC so far?

Along with WHOs announcement on 8 May 2018, the Government of the Democratic Republic of Congo issued an outbreak declaration in the country, warning citizens of newly confirmed cases of Ebola virus disease EVD). At the time of announcement, only two suspected cases were officially confirmed via laboratory testing. An additional 7 cases have since been identified by the DRCs Ministry of Health. This number could rise in the days and weeks to come.

Healthcare workers initially raised the alarm, so to speak, when a number of patients began displaying the most common Ebola virus symptoms. Concern grew when some patients also displayed haemorrhagic indications of the disease (exhibiting internal and external bleeding and bruising). Many of the patients admitted for care appeared to have had contact with at least one other suspected case.

Samples were collected – 3 from the Ikoko-Impenge health facility (about 30km from Bikoro) and 2 from Bikoro – and sent to the capital of the DRC, Kinshasa for analysis. The analysis was conducted by the Institute National de Recherche Biomédicale (INRB) on 7 May 2018 and 2 samples were confirmed as Ebola virus the same day.

A total of 39 cases (including at least 3 healthcare workers) of confirmed and suspected (and probable) Ebola virus were reported between 4 April and 13 May 2018. Nineteen of these cases resulted in fatalities (49%). The number of new cases, however, appears to be rising – now standing at 42.

The majority of identified cases have been from the Bikoro health zone, along with several others in the Iboko and Wangata health zones. This week, the health minister, Oly Ilunga Kalenga confirmed that one case has been reported in the city of Mbandaka, sparking fears of an increase in potential new cases.

For the time being, at least 393 reported contacts have also been identified for follow-up in the event of further outbreaks due to probable exposure risk. (3) Handling of the outbreak is currently being coordinated by the country’s Ministry of Health, working closely with:

- The WHO (the World Health Organization)

- MSF (Médecins Sans Frontières / Doctors without Borders)

- WFP (The World Food Programme)

- The International Federation of the Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies

- UNICEF (United Nations Children's Fund)

- UNOCHA (United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs)

- MONUSCO (The United Nations Organization Stabilization Mission in the Democratic Republic of the Congo)

- IOM (International Organization for Migration)

- Africa CDC (Centers for Disease Control) and US CDC

The coordinated effort is helping to mobilise all healthcare teams conducting response operations in a similarly effective way as was done during last year’s outbreak. A multidisciplinary team that coordinated efforts in a comprehensive way during the outbreak in 2017 certainly strengthened the ability to better contain the viral disease and facilitate surveillance investigations. A similar coordinated effort has been put into effect now with the hopes of being able to achieve the same result – rapid containment of the Ebola virus. The priority in all disease outbreak instances is to rapidly control suspected and confirmed disease cases and reduce any further loss of life.

As has been learned from past outbreaks, quick containment is reliant on timely alerts to authorities as soon as suspicion of infection with the disease surfaces within a medical set up, immediate and appropriate testing being conducted, public announcements being made once cases are verified, access to flexible funding being granted, assistance responses from local and international partners / organisations and the arrangement of supportive teams being swiftly implemented.

Since the initial cases of the latest outbreak were reported and confirmed, with more suspected, many of which believed to be probable based on the nature of symptoms and other proximity factors, the WHO released US$ 1 million from the organisation’s Contingency Fund for Emergencies to initiate assistance efforts to the DRC for the next few months. The UN also supplied US$ 2 million from their Central Emergency Response Fund.

Response teams within the DRC are actively working to verify all related information on any cases reported to the health department. A coordinated approach is aimed at strengthening the effectiveness of the response effort within the affected towns and villages, and by extension the country at large.

Around 50 public health experts and personnel (which make up the rapid response teams), along with necessary supplies and equipment, have already been deployed by WHO to provide additional support to the DRCs local Ministry of Health who are already actively working to gain the upper hand on the outbreak in affected areas. The deployed rapid response teams are also providing technical and operational support so as to help coordinate efforts at every level needed. These teams consist of clinicians, epidemiologists, infection prevention and control experts, logisticians, risk communications experts and now, vaccination support individuals.

Teams are actively managing contact tracing surveillance (verifying new or potential cases), implementing treatment for existing cases (confirmed, probable and suspected), engaging with local communities in order to create extensive awareness about the outbreak, coordinating response efforts from all parties involved and ensuring that all burials are conducted safely and in a dignified manner.

The MSF has established a treatment centre in the Bikoro health zone, specifically for managing suspected and confirmed cases of the Ebola virus. Risk communication materials have also been provided and distributed by WHO in French and the Bantu language, Lingala, which is widely spoken throughout north-western DRC. These materials help to better educate the population regarding what to do if illness is suspected and how to go about preventing infection.

The United Nations Humanitarian Air Service (UNHAS) has ensured that an air-bridge is now in place between the cities of Kinshasa and Mbandaka, and the more challenging to reach areas affected by the outbreak so that supplies, equipment and teams of experts can be airlifted and delivered quickly, ensuring that aid reaches where it needs to be as timeously as possible. Flights are currently running daily between Kinshasa and Mbandaka, and Mbanadaka and Bikororo

On 13 May 2018, WHO Director-General Dr Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus visited Bikoro in order to assess the nature of the active responses currently in place, as well as determine whether additional support is required. Dr Tedro was accompanied by the WHOs Regional Director for Africa (Dr Matshidiso Moeti), and Deputy Director-General, Emergency Preparedness and Response (Dr Peter Salama).

While visiting the country, Dr Tedros met the country’s President, Mr Joseph Kabila and Dr Oly Ilunga Kalenga. A review of the steps implemented so far, as well as those necessary in the coming days and weeks and months were discussed.

“In Bikoro, I saw first-hand the efforts the national health authorities and all our partners are investing in rapidly establishing the key elements of Ebola containment,” said Dr Tedros.

The Director-General also conveyed praise for how the country’s authorities have swiftly handled the outbreak since it was identified, especially since many cases are not too far from urban centres with larger populations. Dr Tedro, congratulated the DRC’s government leaders for how quickly a declaration was made, warning its citizens, and by extension the remainder of the world.

Further aid funding requirements have also been highlighted since the visit. The WHO estimates that international response funding to the value of US$ 18 million may be required for the next several months. The DFID (UK Department for International Development) and the Wellcome Trust in the UK have announced committed assistance in this regard. The Wellcome Trust has already committed £2 million to aid in any critical research requirements to enhance the operational response already underway.

The WHO along with the DRCs Ministry of Health and MSF are now in the process of providing experimental vaccination supplies to the outbreak areas. The vaccine is known as rVSV-ZEBOV (recombinant vesicular stomatitis virus–Zaire Ebola virus) and has been involved in several clinical trials to date.

The experimental vaccine was developed by Canada’s Public Health Agency and is a licensed product of Merck & Co. It is yet to be officially licensed for actual use, however. The vaccine does not contain the live Ebola virus at all. Instead it contains vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV), a harmless virus which is capable of encoding the Ebola virus surface protein and thereby replacing it in the body.

In 2017 SAGE (the Strategic Advisory Group of Experts on Immunization) advised that if any further outbreaks occur before the vaccine is officially licensed for use, it should be deployed if all concerned parties agree and provide informed consent.

The Congolese government (DRC) has agreed to allow the WHO to begin importing the vaccine into the country so as to assist with current response efforts. All formal requirements that include the vaccine registration and import permits have been completed. Approval for the vaccine import was given by the WHOs national regulatory authorities and ethics committee

The WHO has a small stockpile of the vaccine which can be used. Merck & Co. have also agreed to supply the WHO with more as soon as possible so that the import agreement can be fulfilled. As of 16 May 2018, around 4 000 doses have reached the DRC for use.

All teams involved will work together to ensure that logistical constraints do not get in the way of being able to supply the vaccine to the affected areas so as not to delay the much-needed support.

The teams on the ground have been advised that the delivery strategy for vaccination will be by ‘ring vaccination’. The strategy thus aims to protect individuals at all levels of exposure risk, particularly those in the high to moderate categories. Each risk category is considered to be ‘a ring of eligible candidates’. All individuals who are considered at risk are eligible for vaccination – including those known to have been in contact with suspected or confirmed cases to date, as well as anyone else who has been in contact with them (contacts and contacts of contacts), as well as all healthcare and front-line personnel (both local and international) operating in the affected areas, and those living and working in areas of moderate risk.

All initial vaccinations will receive follow-up checks in the weeks and months to come, ensuring that the outbreak has been sufficiently contained. Vaccinated individuals can expect at least 6 health checks between 3 and 84 days after receiving the vaccination. Vaccinations will be freely available and offered in a voluntary capacity but are likely to be heavily encouraged. Vaccinated individuals will be advised of all possible immunisation side-effects which may be expected during the initial few days. These can include:

- General malaise

- Cold-like symptoms

- Mild fever

- Some swelling at the vaccination site may also occur.

Symptoms are likely to be transient and resolve within a matter of days. An allergic reaction may occur in rare instances.

All vaccinated individuals will be encouraged to take appropriate precautions so as to avoid exposure to the Ebola virus even though they have received immunisation. General hygiene practice and prevention information will be provided, and these practices encouraged.

In the meantime, until vaccination doses are administered, screening tests in the country’s airports and other entry points are being conducted so as to ensure that any further cases that may place other areas at risk of infection exposure are not missed.

References:

1. World Health Organization. May 2017. Frequently asked questions on Ebola virus disease: http://www.who.int/csr/disease/ebola/faq-ebola/en/ [Accessed 14.05.2018]

2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 14 March 2018. What is Ebola Virus Disease?: https://www.cdc.gov/vhf/ebola/about.html [Accessed 14.05.2018]

3. World Health Organization. 14 May 2018. Ebola virus disease – Democratic Republic of the Congo: http://www.who.int/csr/don/14-may-2018-ebola-drc/en/ [Accessed 14.05.2018]