A study that has been running for 13 years has published a report showing that the risks for atrial fibrillation are significantly reduced with moderate chocolate consumption. That’s between 2 and 6 ounces or 56 and 170 grams of chocolate consumed each week – and the benefit?

The report finds that atrial fibrillation (A-fib) risks may be reduced by as much as 20% with controlled portions (servings).

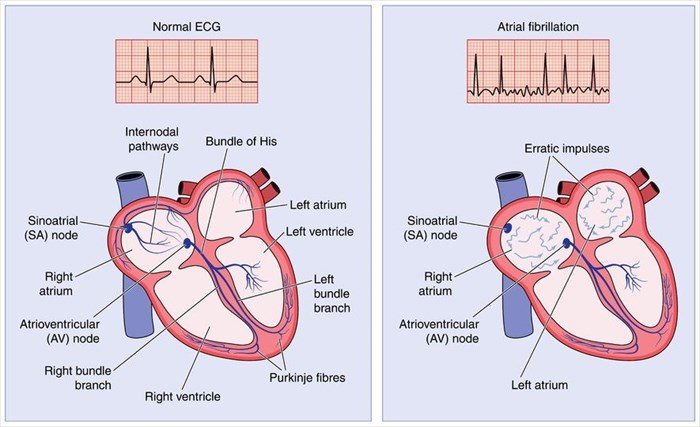

Atrial fibrillation refers to a heart condition with an irregular and often, rapid heart rate. Associated complications with this condition include heart failure, blood clots, ischemia (blood flow blockages) and stroke. A person with A-fib is estimated as being five times more likely to experience a stroke in their lifetime. The condition itself, isn’t typically a life-threatening one, but the risk of complications as a result requires controlled treatment so as to avoid a serious medical problem.

What does atrial fibrillation actually mean?

Basically, the two upper chambers of the heart (the atria) are out of sync, and beat at an irregular pace. A person with this condition will often experience other associated symptoms such as shortness of breath, body weakness and heart palpitations.

The sinus node, which is a group of cells in the right atrium (upper right chamber) functions as your heart’s natural pacemaker, producing impulses that typically begin with each heartbeat. These impulses travel through the atria, and then through all the chambers connecting pathways between all of the upper and lower chambers. As the signal passes through the atria, it contracts. This action pumps blood from the atria into the ventricles (lower chambers or atrioventricular node) below.

When the signal passes through the atrioventricular node (AV node), the ventricles contract and pump blood out to the rest of the body.

When you have atrial fibrillation, the signals quiver, and effectively bombard both atria with impulses as it attempts to reach the ventricles in the lower chambers. This can then also cause the ventricles to beat at a rapid pace, with fewer impulse signals actually getting through.

The average heart rate range for an atrial fibrillation sufferer is approximately 100 to 175 beats per minute. A normal, healthy individual has an average heart beat range of about 60 to 100 beats every minute.

A person can experience episodes of atrial fibrillation that come and go during their life. The condition itself isn’t typically life-threatening but is regarded as serious and requiring appropriate treatment to reduce the risk of potentially severe complications. Treatment focusses on preventing the formation of blood clots and resetting the rhythm of the heart to normal (controlling heart rate) through medications and sometimes surgery.

So, how was the study conducted?

Dr Elizabeth Mostofky, of the Department of Epidemiology at the Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health in Boston, Massachusetts (USA) led the study. The team of researchers included professionals from Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Centre (in Boston, USA), the Aalborg University Hospital, Western University in Canada, as well as the Institute of Cancer Epidemiology (in Denmark).

The findings of the study were recently published in the journal Heart, a peer-reviewed publication with the option for open-access. Being published this way made the study free to read online, making access for news agencies across the world simpler to attain information for write-ups aimed at the broader public. The danger in this is that interpretation may be misguided and non-inclusive of all important facts.

The study, conducted in Denmark, looked at a pool of 55 502 individuals with an interest in chocolate and sought to determine a possible reduced risk of atrial fibrillation, a heart-related condition. The study which spans 13 years of research appears not to have ever been intended to prove any related direct cause and effect, but rather assess the possibility of lowered risk with varying quantities of chocolate consumption.

All individuals involved in the study were adults. Initially the study recruited participants between 1993 and 1997. Each participant had their blood pressure, cholesterol levels and BMI (body mass index) measured, among other things. Each participant was also requested to complete a variety of questionnaires covering areas of diet, overall health and lifestyle. Using this data, the team of researchers were able to create a base on overall health and chocolate intake from which to start their research.

From the Danish National Patient Register, the research team was able to identify a total of 1 346 cases of A-fib from the total number of participants. These individuals were assessed during follow-ups for the next 13 and half years.

The findings in a nutshell (according to the study)

Initially, participants who consumed 1 ounce (one serving) or 28 grams of chocolate during a month had only a 10% risk of experiencing A-fib episodes when compared to those who consumed between 1 and 3 ounces or 28 to 85 grams in the same period. More chocolate consumption appeared to have better results. Could eating more of this sweet treat mean that fewer A-fib episodes may be possible?

Researchers then tested chocolate consumption over shorter periods of time. Select participants ate a serving of chocolate a week. It was concluded that risk reduced even more (17%). Other participants were allowed to consume between 2 and 6 ounces (or 56 and 170 grams) of chocolate a week and their risk was concluded to reduce by as much as 20%. When researchers tried testing daily consumption, risk began to increase. When participants consumed a serving on a daily basis, risk was assessed at 16%. The team’s research appeared to show that the best benefits to be gained were linked with 2 to 6 servings a week.

According to the study findings, which chocolate is best?

It is already well-known that chocolate in general is high in calories due to sugar and fat content. Dark chocolate is higher in antioxidants. These facts are not disputed.

Dr Mostofsky recommends eating the tested servings. Moderation is important. Excessive chocolate consumption will lead to weight gain and other metabolic health concerns. The best chocolate to indulge in would be that which has a high cocoa content, and less calories. Cocoa has already been linked to lowering risk of heart disease in other studies conducted in recent years.

High levels of flavanols in cocoa-rich foodstuffs, such as dark chocolate, have already been shown to promote better blood vessel function.

The study further supports the healthy benefits of moderate dark chocolate intake and overall heart health. The benefits are only really effective when included in an already balanced, heart-healthy diet. If the rest of your diet is not nutritious, benefits will be cancelled out.

Dr David Friedman, a Cardiologist at Northwell Health’s Long Island Jewish Valley Stream Hospital (in Valley Stream, New York, USA), added that although the study does appear to show limitations (i.e. many participants had no other serious health concerns such as diabetes) when it comes to the link between higher intake of heart-healthy chocolate choices and lowered risk of A-fib episodes. He stressed that cardiovascular health in general must factor in far more than just chocolate. An overall nutritious diet and regular aerobic exercise form part of healthy lifestyle behaviours that contribute to benefitting a person with such a condition.

Dr Rachel Bond from the Lenox Hill Hospital in New York City, agrees with Dr Friedman regarding noted limitations of the study, and adds that medical concerns or conditions such as diabetes and hypertension (high blood pressure) typically experience atrial fibrillation too. “It’s hard to say whether eating chocolate was protective or if this population is less predisposed to irregular rhythms,” she says.

So, what if a person does have other health conditions?

This is the big question many appear to have concern about since reading the report, and possibly feel that the study does not answer effectively enough. The grey areas centre around the nature of participants and whether there is a direct link between cause and effect at all, especially where health conditions are concerned.

Conditions many experts have voiced concern about relate to existing diseases and disorders such as cardiovascular disease, hypertension (high blood pressure) and diabetes. These conditions are all high on the list of risk factors for developing an irregular heartbeat and aren’t likely to benefit from chocolate consumption at all. Chocolate intake is more likely to aggravate symptoms, leading to higher risk of further complications, instead of achieving the opposite. Many strongly feel that this hasn’t been sufficiently factored into the research process. Individuals who receive treatment for these conditions typically avoid this sweet indulgence in order to better preserve their health, so as to avoid overindulging which can trigger aggravating symptoms.

Another counter-argument is that the study doesn’t effectively address whether eating dark chocolate in moderate portions will actually alleviate atrial fibrillation symptoms if you’ve already been tested and diagnosed with the condition itself.

The chocolate versus heart health debate

So, what is all the fuss with the latest report?

The accuracy of facts is being hotly debated. Counter-arguments were voiced and published almost immediately after the report was made available.

The report, which focuses on chocolate being a favoured form of indulgence, was quickly picked up by media worldwide, making headlines everywhere. The focus of these headlines highlighted the intention of the report findings – meaning ‘chocolate may be good for you’. For the general public, this translates as ‘chocolate is good for you’ and will be taken as a single truth without reason to question all contributing factors that led to the statement perception. Interpreted literally, this conveys a strong notion that this has been conclusively proven through science. Counter-arguments wish to stress that this is not necessarily the case.

Many in the medical field soon began asking questions once the report was published, particularly when it comes to a direct link between cause and effect. It appears the report displays several grey areas.

The study was funded by grants from credible institutions including the European Research Council, the US National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute, the EU, the Danish Cancer Society, the Danish Council for Strategic Research and the Harvard Clinical and Translational Science Centre. Credibility does not appear to be disputed on this front.

Other than certain health conditions and the effects of chocolate consumption on associated symptoms, obvious limitations and grey areas point out the following:

- The study is a prospective cohort study: This type of study is generally accepted as being useful for determining specific patterns, but the findings are not used specifically to prove that something directly causes another. In this case, this means that the study findings shouldn’t be interpreted as ‘the consumption of chocolate directly reduces the risk of developing episodes of atrial fibrillation’.

- The data isn’t the same for all participants: All participants recruited, men and women, were between the ages of 50 and 64. Confounding factors taken into consideration for each narrowed down for the A-fib study included their sex, blood pressure, BMI, total cholesterol and total calorie intake, as well as other details such as individual coffee consumption, applicable smoking habits, education level, and whether each had existing conditions such as hypertension, other cardiovascular conditions or diabetes. The research did factor in possible confounding factors. The research was conducted to produce separate sets of results for both men and women. Men appeared to have a lower risk if they consumed 2 to 6 servings of chocolate and week. Women, however, appeared to have a lower risk if they consumed a serving once a week in comparison. The differences regarding lower risk between the sexes, however, are noted as being small. It is also noted that fewer women in the study have A-fib. This does influence the overall findings of the report.

- Data based on self-reported consumption: Accuracy has also been debated as the study report stipulated that all participants ‘ate chocolate’ and ‘self-reported’ the quantities. The report does acknowledge the limitations of this by stating that “As with any study using self-reported exposure information, there is a concern of poor recall.”

- Interpretation of the results: To be fair there are many merits to the study which rest on the back of others conducted that have shown benefits regarding some compounds found in dark chocolate being helpful to a person’s cardiovascular system. Flavanol content has been scientifically shown to improve heart health, and as a compound can lower high blood pressure levels, as well as assist with regulating blood clotting. With flavanol (antioxidant) content comes the more fattening properties of chocolate (i.e. calorie components – fat and sugar) which pose health concerns worth noting, especially if the milk varieties of chocolate are being consumed. These varieties typically have higher calorie content. So, in the interpretation of data results, the question begs, ‘how helpful are the benefits of the chocolate consumption?’ The confounding factors have been debated as to whether they are statistically all that significant or not. The reason behind this is in how the final data was presented – according to a method called ‘hazard ratios’. These ratios are effectively numbers that assess, in this instance, the risk of getting a disease based on two separate experimental groupings. Each group will be tasked with different actions to assess. So, if one group is given portions of chocolate to consume and the other, none at all, differences can be assessed according to the objectives of the study. If the group consuming chocolate had to develop heart disease, the hazard ratio will be determined as 0.9. If no difference is noted, the hazard ratio between the two groups would be determined as 1. A ‘confidence interval’ is then attached to this ratio as a means of calculating possible error as a percentage. If a hazard ratio is 0.9 with a 95% confidence interval of 0.85 – 0.95, this effectively means that there is a 95% chance that the actual ratio is 0.85 – 0.95. A ratio below 1 indicates findings without increased risk. If the confidence level is higher (over 1), this means that a person then has an increased risk of developing a health condition. So, if the confidence levels are between 0.85 and 1.05, risk increases to 5%. Why then are some experts viewing the data interpretation in this study as statistically insignificant? It comes down to the confidence intervals that include 1 in its range. The study shows half the participating groups having had confidence intervals that crossed 1. Simply put, half the group may not actually have shown a decreased risk of A-fib at all, but rather a small percentage of increased risk instead.

- The chocolate used in the study: Another voiced question mark relates to the type of chocolate used in the study. It’s been pointed out that European chocolate is typically produced with higher amounts of cocoa than say, American varieties. As such, the participants consumed chocolate that had higher levels of flavanols. If flavanols are the benefitting factor in chocolate, is it not better to rather consume fruits, vegetables and tea that contain the same compound, and none of the sugar and fat found in many other product varieties?

So, is moderate consumption of chocolate good for you or not?

There are benefits of this study and there is no doubt that it was conducted by reputable institutions and qualified individuals. The study itself was a sizable one and took many important aspects into consideration, including the various confounding factors. But is chocolate the magic ingredient for heart health? The chorus of voices since the publishing of the report indicate ‘not exactly’.

There are factors that indicate a potential lowered risk, but there are many others that may indeed point to a small margin of increased risk too. Science appears to prove both ways, for various reasons and taking specific details (in isolation) into consideration. Certain foodstuffs, like chocolate may have a small, but positive impact on certain medical conditions. Antioxidant properties in cocoa do have some positive impact on cardiovascular health. Ultimately, though, any beneficial impact may not mean much if overall health is not in good condition. A balanced and nutritious diet, as well as regular aerobic exercise ultimately count for far more when it comes to heart health than just a regular intake of dark chocolate.

It is not agreed by all that the study conclusively shows that moderate dark chocolate intake prevents episodes of A-fib (and lowering risk). There is no clear, direct cause and effect link. Those with the condition or who have associated risk factors (such as an existing condition like hypertension which places them at higher risk of A-fib episodes) should perhaps avoid consuming chocolate, and discuss their diet in detail with their primary healthcare provider (general practitioner or GP) or medical specialist before including more or less of something (including chocolate) in their diet. Anyone with an existing health condition must factor in the negative compounds of chocolate – being fat and sugar – and the impact this will have on their overall health, irrespective of the flavanol content.

In general, there’s little to be concerned about when consuming chocolate in small portions as part of a balanced and nutritious daily diet. The idea that chocolate is a ‘superfood’ for heart health is quite possibly a little misguided. It’s not agreed that chocolate on its own impacts levels of risk all that greatly to be considered a preventative ‘superfood’.

Those with medical conditions (or without) may be better off working with their healthcare providers to develop the most nutritious daily meal plan possible, which may or may not include a small amount of sweet indulgence from time to time.