For women, in particular, breast cancer has a high incidence rate and is somewhat difficult to treat in its advanced stages. So, when a woman with advanced stage breast cancer is making headlines as being completely cleared of the disease following a ‘ground-breaking therapy’, the world is sure to sit up and take notice…

It’s being reported as the first time a woman with advanced stage breast cancer has shown such a positive treatment outcome following an experimental round of immunotherapy. This comes after the research team of doctors behind her successful treatment published their findings in the journal, Nature Medicine earlier this month. (1)

An engineer from Florida, USA, Judy Perkins was diagnosed with breast cancer in 2013. It wasn’t her first encounter with cancer. Ten years prior, Judy had discovered a lump and received her first diagnosis. Following a mastectomy, it seemed that she had gotten the better of the disease. Then in 2013, it seemingly returned and this time with a vengeance. The diagnosis was stage four. Judy had been through as many as 7 rounds of chemo and hormone therapy to treat the tumour in her right breast in an attempt to prevent the disease from spreading. Despite undergoing treatment, more tumours developed. Her cancer was more aggressive, and the prognosis was not good.

The therapies used had failed to prevent the cancer from spreading to her liver, and with that, any hope of curing her disease plummeted. The tumours began pressing against a nerve which caused her a great deal of discomfort and shooting pains in her arm. Judy quit her job and resolved to let go of her dreams and ambitions as she felt that since ‘her time was nearly up’, there was no need to put up a fight.

“I was planning on dying,” she says.

In 2015, Judy was selected as a participant in an experimental treatment procedure (as part of an ongoing clinical trial), and little did she know that it would be her saving grace. She received treatment at the National Cancer Institute (NCI) in Maryland, USA and responded well. The therapy has seemingly helped to eradicate the cancer cells within her body. Now 52 years of age, Judy has been declared cancer-free for the past 2 years and she’s already piecing her life back together.

Has medical science found a way to potentially cure breast cancer?

As one of the leading causes of mortality worldwide, this is a serious question to ask and answer. The idea that a treatment process can get the better of such advanced and aggressive cancer has sparked some degree of hope in oncology circles, but can medical professionals really get excited just yet?

The therapy used to help treat Judy’s advanced stage breast cancer basically used her very own immune system in order to fend off cancer cells in her body. This has long been an area of interest in cancer treatment and is not the first of its kind to be developed, tested or even used. However, the modified method of immunotherapy employed by this team has seemingly achieved success in a patient who was classified as most likely terminal.

This form of immunotherapy sounds simple enough in theory – in practice, it’s considerably more intricate. It is technically complex to make use of the body’s own immune system and the methods for this type of treatment implementation are currently expensive.

So far, the best-case scenario has been achieved in Judy’s case, but could it work for other patients with advanced breast cancer? Could it work for other difficult to treat cancers, which also have high mortality rates – like prostate and ovarian cancer? These are even bigger questions, and as yet, there aren’t any conclusive answers.

In theory, it may be possible, but it is important to note that the treatment was not a success in all of the candidates involved in the recent trial. This new approach is still in the experimental stages and the results are considered preliminary. Finding the answers to the bigger questions is still part of ongoing research which may be some way off from receiving the official stamp of approval for standard treatment use.

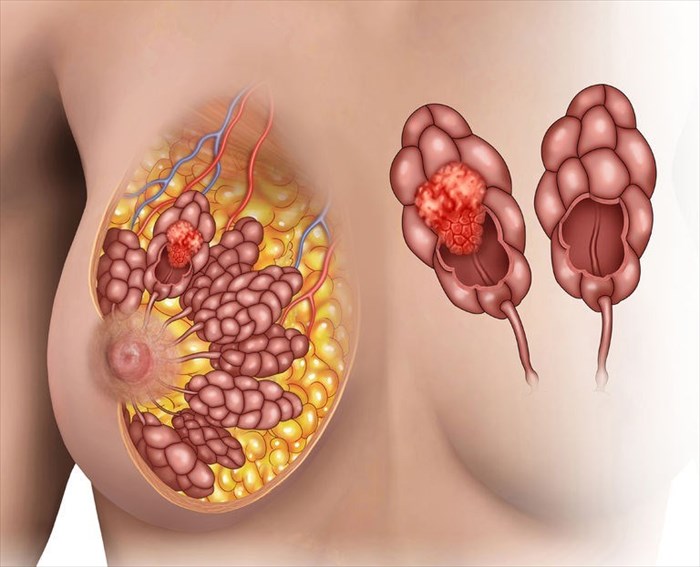

The success achieved is, however, intriguing. After all, ovarian, prostate and breast cancers (and others) are typically difficult to treat since there are often few detectable cell mutations to target with treatment. As such, the immune system struggles to detect malignant cells among the healthier ones in order to eradicate them. Cancerous cells then easily overpower healthier cells, spreading further. This is partly why all of these types of cancer are listed among those with the highest mortality rates. The modified therapy used in the new approach is almost ‘personalised’ for a patient, using their very own cells to help treat the disease.

Yes, this treatment has seemingly cleared Judy’s advanced stage disease, but it does need to be put to the real test – i.e. a series of full scale clinical trials involving more patients. More work beyond the current trial may be needed to prove this method as a safe and effective treatment option. If it is to be routinely used in future, bigger trials must conclusively prove this for various patients, types and stages of cancer.

An in-depth look at the new breast cancer treatment approach

The therapy used to treat Judy’s condition is called T-cell immunotherapy and is a modified version of ACT (Adoptive Cell Transfer). As another form of immunotherapy, ACT has achieved some treatment success for various cancers, but has been noted as less effective when it comes to more advanced or difficult to treat forms. The treatment of cancers, like those that originate in the lining of organs or typically have fewer mutations haven’t achieved high success rates with ACT. Researchers appear to favour T-cell immunotherapy as a potential option for this very purpose. It is their hope that this form of immunotherapy will be able to successfully treat these challenging conditions more consistently.

T-cell immunotherapy works in phases as follows:

- Tumour biopsy: Small samples of tumour tissue are extracted from the body of the patient.

- Immune cell extraction: Immune cells that have penetrated malignant tissues (tumours) are then extracted from the biopsied tumour tissues. This process is known as the harvesting of tumour infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs). Immune cells tend to infiltrate malignant cells as a natural response to disease – the purpose of this is to kill off the abnormal cells. However, the immune cells are often too few or too weak to achieve this purpose in cancers of the breast, for instance, but they are present. Once extracted, these cells are grown in a laboratory – producing billions of cells, effectively creating something like an immunological army “ready for combat”.

- Gene sequencing: An analysis of cell tissue DNA helps to identify specific mutations within cancerous tumours which typically create various abnormal proteins within the malignant cells.

- Screening of immune cells: Once specific mutations have been identified, the immune cells extracted from the biopsied tumour/s are then screened to determine which ones will most likely be able to be used for tumour cell targeting (i.e. which immune cells are likely to ‘recognise abnormal proteins’ in tumours so as to kill off the malignant cells present).

- Cell infusion: Immune cells (in their billions) are then infused back into a patient where they can get to work on ‘attacking targeted malignant cells’ and eradicating them.

In Judy’s case, doctors were able to identify around 62 mutations from the biopsied tumour tissue during the sequencing phase. (2) Around 80 billion laboratory grown immune cells were infused back into her body in order to help eradicate her malignant tumours.

Along with the T-cell immunotherapy, Judy was also given a commonly used antibody, Pembrolizumab. This medication is sometimes prescribed for cancer patients. The drug is intended to stimulate immune cells, so as to promote the eradication of malignant tumour cells. The drug on its own is not generally known to be all that effective in the treatment of advanced stage breast cancer. Nevertheless, the research team specifically prescribed the drug to prevent any possible inactivation of the infused immune cells inside the tumour.

Within the first 6 weeks, the research team found that Judy’s ‘target tumour burden’ had declined by around 51%, showing that the infused cells were effectively doing their job. (3) This in itself, restored hope – both for the treating medical team and Judy. Regular tests during the first 17 months showed the presence of the infused immune cells in Judy’s body. Within 42 weeks, Judy was cancer-free. During the following 22 months, her cancer did not return and has not since (now almost 2 and half years later). For Judy, this is nothing short of miraculous. One moment she was certain her days were numbered, the next, plans could be made and ambitions realised. She is also now leading a normal, everyday life… For her, these doctors restored purpose– from day-to-day living to fulfilling her bucket-list of things to achieve.

The team of treating doctors at the US National Cancer Institute, headed by Dr Steve Rosenberg (Chief of Surgery at the Center for Cancer Research at NCI) remain cautiously optimistic about their approach’s potential. There is much work to do and the next steps are already in progress as T-cell immunotherapy is being used as part of ongoing study. Judy’s treatment is proof of possible success. An ongoing clinical trial is looking at whether tumours can be eradicated in other types of difficult to treat cancers – including those in the breast/s, ovaries, endometrium, urothelium and digestive tract. (4)

The team acknowledge that the research is highly experimental, but also highlight its potential to possibly become a viable treatment option for cancer patients in the future. The therapy focuses on malignant mutations rather than the specific type of cancer. All cancers display characteristic mutations and cell abnormalities. It is these mutations which the research team feel can serve as the best targets in order to eradicate disease. So, theoretically, T-cell immunotherapy could be used for many different types of cancer, and not just those located in the breast, prostate and ovaries. Liver, colorectal and stomach cancer tumours may also benefit from research trials using this therapy.

There may not yet be a readily available cure on the horizon as yet, but there’s certainly promise. For now, Judy’s success is the shining light. It will be interesting to see if more results like those in Judy’s case can be achieved using this method of treatment. If they can, it may just be a foreseeable possibility that advanced stage cancer, like that of metastatic breast cancer, could potentially become curable. It’s promising, and patients and doctors alike will surely welcome such results. After all, treatment for such advanced stage illness could just save many more lives…

References:

1. Nature Medicine. 4 June 2018. Immune recognition of somatic mutations leading to complete durable regression in metastatic breast cancer: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41591-018-0040-8 [Accessed 14.06.2018]

2. National Institutes of Health. 4 June 2018. New approach to immunotherapy leads to complete response in breast cancer patient unresponsive to other treatments: https://www.nih.gov/news-events/news-releases/new-approach-immunotherapy-leads-complete-response-breast-cancer-patient-unresponsive-other-treatments [Accessed 14.06.2018]

3. Nature Medicine. 4 June 2018. Letter - Immune recognition of somatic mutations leading to complete durable regression in metastatic breast cancer: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41591-018-0040-8.epdf? [Accessed 14.06.2018]

4. ClinicalTrials.gov. 3 August 2010. Immunotherapy Using Tumor Infiltrating Lymphocytes for Patients With Metastatic Cancer: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01174121 [Accessed 14.06.2018]