When it comes to diet and nutrition, too much of this and cutting out that is an all too familiar routine for many of us nowadays.

Bloggers and health enthusiasts are sprouting up everywhere, creating very convincing brands and all have a theory (or programme of some sort) ‘that really works’. While much of it can make a positive difference, there is possibly no such thing as a ‘one size fits all’ diet for everyone.

With health conditions like obesity tipping the scales all around the world and increases in cardiovascular troubles, societies are well tuned in to any information available that promises to help us out with ‘what we should be eating for optimum health’. From books to blogs… celebrities and health gurus (including the medically qualified variety), all punting their unique winning formulas… there’s little out there that many haven’t tried. Whether good or bad, the final outcomes are generally relative and depend on a variety of different factors.

For most of us, achieving a healthy balance often comes down to preferences or circumstances which spark a change, like the development of a health condition. Personal preferences and overall health often guide us down the eventual paths we choose.

Whatever your choices, it can be difficult to know exactly what to eat, how frequently and in what quantities. Should we be incorporating a little bit of everything or are some foods so toxic they shouldn’t feature at all?

Recently, the sweetness has been knocked right out of sugar and the harmful effects associated with its use are making headlines everywhere. Refined anything is a huge ‘no-no’ too, enjoyable as such foods might be. Low carb, low fat, no fat, sugar free… the bandwagon of what to eat and what not to eat is certainly in motion, and opinions abound.

This week, it’s eggs that are in the spotlight, and not for terribly off-putting reasons either. If this latest study is anything to go by, it may just be time to start (if you’re not already) ‘getting eggy with it’ – yolk and all.

Eggs and your health

You might love them or hate them. You may even prefer their white and yolk components separately. Some may simply view eggs as an ingredient that is best enjoyed in baked products. Preferences aside, there’s nutritional benefit within the entire egg.

Beneath their shells, eggs are very good sources of high-quality protein, vitamin A, vitamin B12, vitamin D, vitamin E, folic acid, iron and antioxidants. The yolks also contain the water-soluble nutrient, choline which is associated with healthy brain development. The fats and micronutrient content in eggs contribute to overall healthy nutrition when regularly incorporated into one’s diet. The balance of goodness can be tipped, however and how you eat this versatile foodstuff makes a difference, but there’s no denying that eggs themselves can be a healthy addition to anyone’s diet.

Eggs have received some bad press over the years though. Cholesterol content is one reason some people steer clear or limit their intake. Just one large yolk could amount to as much as two thirds of a person’s recommended daily intake of cholesterol. (1) Eggs alone can’t contribute to high cholesterol levels, however. There are many other contributing factors in this regard. Other reasons eggs may be omitted from a diet relate to a fear of salmonella bacterial infections (most associated with undercooking) or simply because of an allergy.

Taking nutritional benefits into consideration alongside ever-increasing numbers of newly diagnosed health conditions, studying food is fairly common practice these days.

The research team from the School of Public Health at Peking University Health Science Centre (PUHSC) in Beijing, China recently published their study findings (in the British Medical Journal, Heart) in relation to eggs and their nutritional benefits. The focus of their study was not necessarily to highlight nutritional benefits on their own as such, but more specifically to analyse consumption frequency and a potential link to lowering risk of cardiovascular disease, ischemic heart disease, stroke (ischemic and haemorrhagic) and major coronary events, like heart attack. (2)

Why? Cardiovascular disease is now one of the world’s leading causes of illness, disability and death. Dietary factors are but one of many contributing factors in this regard, and the study does acknowledge this. Other factors which play a role include smoking habits, alcohol consumption and even a lack of physical activity. Age and gender also have a role to play.

The research from this team of experts is not the first of its kind. A study conducted in 2013 also looked at egg consumption and a dose-response analysis in relation to coronary heart disease and stroke. A high consumption of eggs was measured at (up to) 1 a day and researchers concluded that this was not a contributing factor to increased risk of heart disease and stroke. (3) The current research appears to concur with this.

How was the study conducted?

The latest study, referred to as the China Kadoorie Biobank (CKB) study, initially assessed over half a million (512 891) adult participants, ranging between 30 to 79 years of age. The initial assessment period took place between 2004 and 2008. Re-surveys (or follow-ups) were also conducted thereafter. Participants were recruited from at least 10 geographical survey sites in and around China – including five urban and five rural areas.

During the participant selection process, the research team excluded individuals who had a medical history of cancer, stroke, heart disease and prevalent diabetes. Two individuals were also excluded who did not have recorded BMI (body mass index) values. This brought the final participating number down to 461 213 individuals who were deemed eligible for analysis. Participants signed consent forms in order to start the analysis process.

The CKB study was then approved by the Ethics Review Committee of the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention, in Beijing, China; and the Oxford Tropical Research Ethics Committee at the University of Oxford, in the United Kingdom.

In order to begin an analysis, participants received a qualitative food frequency questionnaire aimed at detailing their habitual egg consumption habits during the previous 12-month period. Frequency period options included daily, 4 to 6 days a week, 1 to 3 days a month, rarely and never. Select participant groupings were randomly chosen for periodic follow-up interviews every 5 months or so. Follow-up surveys were extended into 2014.

The questionnaires also collected information relating to sociodemographic data (age, gender, education level, income and marital status), as well as lifestyle behaviours (such as alcohol consumption, smoking habits, intake of supplements and multivitamins, physical activity and consumption of other foodstuffs including rice, fish, dairy, poultry, red meat, fresh and preserved vegetables and fruit). Medical history and family medical history also formed part of the questionnaire data collected.

Participants were all measured by trained representatives so as to collect body weight, height, hip and waist circumference, and blood pressure data.

During the analysis periods relevant mortality information relating to participants was obtained from local disease and death registries on a regular basis. This information was also checked against the national health insurance system and hospital records.

What were the findings?

The average age of participants was around 50 years old. A total of 41% were male. Around 42% of the total population group eligible for analysis lived in urban areas. Approximately half of the urban participants consumed eggs between 1 and 3 times a week. It was noted that participants who consumed eggs regularly had a higher education level than those who rarely or never ate the foodstuff. Higher education levels were also consistent with more well-off household incomes. These participants were also more likely to take multivitamin supplements and indulge in more affluent dietary habits.

At least 13% of the participants listed daily consumption of eggs (around an average of 1 a day). Around 9% of participants reported rare consumption or not at all. This distinction enabled the researchers to group participants as either ‘consuming’ or non-consuming’ for comparative analysis.

During the analysis period, the research team noted a total of 83 877 cases of diagnosed cardiovascular disease. Of these 30 169 were ischemic heart disease, 7 078 haemorrhagic stroke and 27 745 ischemic strokes. A total of 9 985 cardiovascular disease cases were recorded as deaths, 3 374 of these were attributed to ischemic heart disease, 3 435 haemorrhagic stroke and 1 003 ischemic strokes. There were also 5 103 major coronary events recorded.

When comparing egg consumers with non-consumers, the research team determined that more regular consumption (i.e. daily consumption) appeared to be associated with a considerably lower risk of cardiovascular disease. The team, however, could not find a significant different between consuming 1 egg a day or two per week when it came to reduced risk for cardiovascular disease. Overall, the regular consumption of eggs appeared to reduce risk to some degree.

Daily (more frequent) egg consumption (at least 5.32 eggs per week) appeared to show a 12% lowered risk of ischemic heart disease when compared with rare (no more than 2 eggs consumed in a week) and non-consumers. This study allowed for some distinction to be made between stroke subtypes and appeared to be consistent – finding that at least 1 egg consumed daily could reduce risk of both haemorrhagic and ischemic stroke. With each egg consumption increment, risk could be lowered by as much as 8%. Hypertension (high blood pressure) also appeared to be reduced in regular consumers of eggs versus rare or non-consumers.

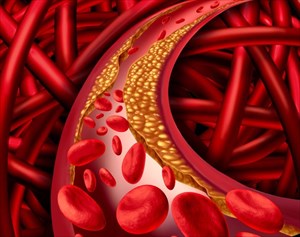

The research team took the cholesterol content of eggs into consideration and surmised that while it was possible for increased consumption to raise levels of low-density lipoprotein (LDL-cholesterol or ‘bad cholesterol’), high-density lipoprotein (HDL-cholesterol or ‘good cholesterol’) could also be elevated. Phospholipids in eggs increase HDL levels and thereby enhance its function by helping to reduce the progress of atherosclerosis (plaque build-up in the arterial walls) which causes heart disease.

In this sense, the ratio between good and bad cholesterol is better balanced, and the team feel that this should not have any direct causal effect on the future development of cardiovascular disease alone (as other risk factors apply to each individual). The team also feel that the overall nutritional components of eggs have a beneficial effect when it comes to optimum cardiovascular health.

The high-quality protein content in eggs has the potential to provide improved satiation. This means that many individuals will feel satisfied for longer and will not likely be indulging in as many snacks between meals. Eggs also help to elevate levels of plasma lutein and zeaxanthin (carotenoids) which are associated with improved cognitive function, but also have a role to play in preventing cell / tissue oxidation (damage), plaque build-up and inflammation.

When looking at the applicable mortality records, the team deduced that daily consumers of eggs appeared to have an 18% lower risk of death due to cardiovascular disease. Daily consumers had a 26 to 28% lower risk of death as a result of haemorrhagic stroke too.

Overall, the research team is confident that their prospective cohort study (the analysis of a group of individuals over time, who have many similarities but some characteristic differences) shows significant data. Their findings show that the risk of cardiovascular conditions can be reduced by increased egg consumption, provided that the overall health of an individual is not negatively influenced by other factors. Overall nutritional health is also important so as not to counteract the positive effects of regular egg consumption.

Due to the use of a large population sample size over an extended period of time the team feels confident in its findings. While the team made provisions for potential risk factors, including stroke subtypes, further studies could help to better determine more precise estimates in terms of the the correlation between egg consumption and cardiovascular heath.

This study is certainly not without its limitations, having relied on a qualitative food frequency questionnaire and survey follow-ups which could not be intensely validated. Egg consumption misclassifications are thus possible – any participant could change their dietary habits including egg consumption, as well as adjust medication or physical activity routines during the assessment period for any reason and the team would be unaware of these developments. Based on the study design, the team feel that they took into consideration as many factors as were within their control but do acknowledge the possibilities of residual factors which could not be measured and thus may have potentially influenced the outcomes. Nevertheless, they feel that if regular egg consumption is adhered to, based on their collected data, the possibility of reduced health risks still exists and can be researched further to support their claims.

So, should we all adapt our diets?

This particular study assessed diet in relation to the average Chinese adult. How such populations enjoy consuming eggs does differ somewhat from how many other Western countries prefer an eggy meal. How a person consumes their eggs can make a significant difference when it comes to overall heart health.

"In a Western context, if you eat eggs with lots of refined white bread, processed meats like bacon and sausages and sugar-rich ketchup, that is materially different to eating an egg with whole-grain bread and vegetables for instance," says University of Cambridge professor, Nita Forouhi.

Not to mention other counteracting factors like significant weight gain or obesity and smoking habits. There are any number of reasons a person can develop cardiovascular conditions. Regular egg consumption would still need to form part of an overall healthy lifestyle in order to truly be beneficial.

The research is largely observational, so it does not provide the general public with a specific ‘diet plan’ that conclusively prevents heart and stroke related medical events. What the research does do is suggest a strong enough link (based on the scale of data collected which serves as scientific evidence, nonetheless) between consumption frequency, taking into consideration the nutritional components of eggs, and overall heart health, which more precisely designed studies could ‘tuck into’ in the future to better outline.

There’s no harm in increasing egg consumption but medical professionals are likely to warn against indulging in too much. There are many other foods which make up a diet that are good sources of protein, for example. Maintaining a diet that is two or even three times the recommended daily requirement of protein can place strain on kidney function. Too much of anything can have a negative impact in some capacity or another, as can too little. A balance of nutrients is certainly ideal for all-round health.

Combinations of food and cooking processes also have an impact. Pairing eggs with foods that are high in saturated fat (like butter) will not counteract bad cholesterol accumulation. Many experts argue that saturated fat content is far more harmful for heart health than the levels of LDL-cholesterol in eggs.

On that note, adding an egg or two into the mix of an already balanced and healthy lifestyle will certainly promote enhanced all-round health. So, if you fancy ‘getting eggy with it’, poached or boiled options will surely make a heart healthy meal and reduce your chances of developing serious cardiovascular conditions. Just remember to go easy on the salt too.

References:

1. Victoria State Government - Better Health Channel. October 2015. Eggs: https://www.betterhealth.vic.gov.au/health/ingredientsprofiles/Eggs [Accessed 25.05.2018]

2. BMJ Journals - Heart. 21 May 2018. Associations of egg consumption with cardiovascular disease in a cohort study of 0.5 million Chinese adults: http://heart.bmj.com/content/early/2018/04/17/heartjnl-2017-312651.info [Accessed 25.05.2018]

3. The BMJ. 7 January 2013. Egg consumption and risk of coronary heart disease and stroke: dose-response meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies: https://www.bmj.com/content/346/bmj.e8539 [Accessed 25.05.2018]