While many human organs can be used for transplant purposes after the donor is deceased, until recently, uterine transplants that gave rise to pregnancies culminating in successful live births were always from living donors.

This has meant that women in need of uterus transplants, either because they were born without one, or suffered a medical condition that resulted in the loss of it, had to rely on a living family member or close friend for the donation if they wished to bear their own child.

While living uterus donors are rare, they do exist and the first successful childbirth following the transplantation of a uterus from a living donor took place in Sweden in September 2013. The field of uterine transplant is therefore still a relatively new one and of the 39 recorded uterine transplants from living donors, just 11 have resulted in successful births.

On the 4th of December 2018, a group of Brazilian researchers published a paper in The Lancet, detailing the first recorded live birth after a uterine transplant from a deceased donor1. Previous attempts at this procedure have been made by teams in the United States, Turkey and Czech Republic, none of which resulted in live birth.

To truly appreciate the magnitude of this research, it is essential to understand what the uterus is, its function and role in fertility and pregnancy.

What is the uterus?

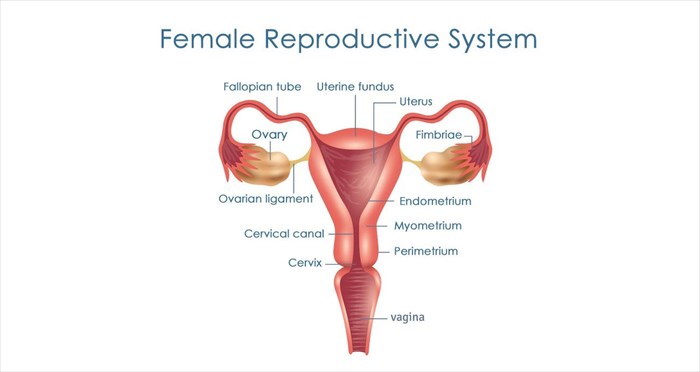

'Uterus' is the medical term for the womb. It is a hollow muscular organ situated between the bladder and rectum in the female pelvis and forms part of the reproductive system.

As part of the reproductive cycle, a woman’s ovaries produce eggs, these travel through the fallopian tubes, and if one (or more) is fertilised, it implants itself into the lining of the uterus, which will aid in the nourishment of the foetus prior to birth.

Understanding congenital uterine abnormalities

It is estimated that 1 in every 4,000 to 5000 females are born with a congenital disorder (i.e. a disorder that is present at birth) known as Müllerian agenesis, also referred to as müllerian aplasia, vaginal agenesis and Mayer-Rokitansky-Küster-Hauser (MRKH) syndrome2.

Medically speaking, agenesis refers to the failure of an organ to develop due to a lack of the necessary cells and tissues required for normal growth and development in the earliest stages of embryonic development.

In these cases, there is an absence or abnormal narrowing of the vagina, uterus or both. Women with this condition are considered infertile, not because they do not ovulate, but simply because no uterus is present, or if a uterus is present, it will be of insufficient size to sustain a viable pregnancy.

Uterine loss – medical reasons for hysterectomy

In some cases, it is medically necessary for a woman to undergo a hysterectomy. A hysterectomy is the surgical removal of the uterus which is usually only performed when all other treatment options for the condition causing uterine issues have been exhausted.

Conditions which may lead to the medical decision to perform a hysterectomy include:

- Uterine fibroids – benign tumours that grow within the uterus and may become very large.

- Endometriosis – a condition which causes the tissue of the uterine lining to grow outside the uterus, leading to chronic pain and bleeding.

- Adenomyosis – a condition wherein the inner lining of the uterus grows into the uterine muscles.

- Uterine prolapse – this condition occurs when the uterus descends through the cervix and protrudes from the vagina.

- Pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) – a serious infection of the female reproductive organs.

- Cancer of the reproductive organs (uterus, cervix and/or ovaries).

The role of uterine anomalies in infertility

Statistics show that 10-15% of couples (that’s an estimated 80 million individuals) of reproductive age battle infertility3. Infertility is regarded as the failure to achieve pregnancy after 12 months or more of unprotected sexual intercourse4. Within this category, 1 in 500 women suffer from uterine issues due to congenital abnormalities, unexpected malformation, infection or hysterectomy.

Prior to the development of uterus transplant surgery, the only options available to affected couples were surrogacy and adoption.

Details of the first successful uterine transplant from a deceased donor

The procedures documented in the recently published case study took place in September 2016. The donor was a 45 year old woman who died from a stroke that resulted in bleeding on the brain (this is referred to as a subarachnoid haemorrhage). The uterus recipient was a 32 year old woman with Mayer-Rokitansky-Küster-Hauser (MRKH) syndrome.

After the donor's uterus was successfully removed it was transplanted into the awaiting recipient during a ten and a half hour surgery during the recipient's blood supply (veins and arteries), ligaments and vaginal canals were connected to the donor uterus.

Recovery from surgery required a two day stay in the intensive care unit (ICU), followed by six days in the transplant ward. A regimen of immunosuppression drugs (drugs that prevent the immune system from perceiving the new uterus as a foreign object and attacking it, thus causing rejection), antimicrobials (medications to kill microorganisms that may cause infection), anti-clotting treatments and aspirin (to prevent blood clots which are common after surgery) were administered to the woman for the duration of her stay. Immunosuppressive treatments were continued after she was discharged.

Five months post-transplant, the woman did not exhibit any signs of uterus rejection, ultrasound scans were normal, and the woman was menstruating regularly – all signs of first stage success.

Four months prior to the transplant, the woman had undergone a single in-vitro (IVF) cycle from which eight fertilised eggs were harvested and cryopreserved (i.e. frozen – more information on how egg freezing works here). Seven months after the transplant the fertilised eggs were implanted. Implantation is necessary in uterus transplants as these procedures do not include a transplant of the fallopian tubes, so eggs cannot pass through these and naturally implant in the uterus when fertilised.

The researchers note that their implantation timeframe was considerably earlier than those which had been conducted before. In previous cases implantation was only attempted after 12 months.

In this case, implantation was scheduled for the six month mark, but at this juncture the endometrium had not thickened as required and the procedure was postponed until the following month.

Ten days after the eggs were implanted, it was confirmed that the woman was pregnant. Prenatal testing at ten weeks indicated a viable pregnancy with normal foetal development, and this was confirmed during scans at the twelve and twenty week mark. The recipient remained in good health until 32 weeks when a kidney infection occurred, she was then admitted to hospital and treated with antibiotics.

At 35 weeks and 3 days, in December 2017, a 2.7kg (6lb) healthy baby girl was delivered via c-section. A hysterectomy was performed during the same procedure in order to remove the transplanted uterus and no abnormalities were present. The mother and child were discharged from hospital three days later and all follow-up examinations were normal.

Notes from the study’s authors

The researchers involved in the study note that a uterus transplant is a major surgical procedure and that in order to qualify, candidateswould have to be completely healthy in order to avoid complications during and after the procedure. In the recently published study, they note using high doses of immunosuppression drugs, which may be lowered in future case studies.

When it comes to the implantation of fertilised eggs, the sooner this can be done, the better, as this reduces the period of time during which immunosuppressive drugs must be taken, thus reducing both side effects and costs.

They further note that transplants using uteruses from deceased donors may have some benefits over those obtained from living donors in that they remove the surgical risks for live donors.

Study conclusion and future transplants

The reported findings demonstrate the viability of uterine transplants from deceased donors. This may give women suffering from uterine infertility renewed hope to bear their own children without the need for a living donor.

While the case mentioned was a success, the outcomes and effects of transplants from live and deceased donors are yet to scientifically compared, and the surgical techniques and immunosuppressive treatments will be fine-tuned in future studies.

According to the research lead on the study, Dr Dani Ejzenberg of the Hospital das Clínicas, Faculdade de Medicina da Universidade de São Paulo, the results achieved provide a proof-of-concept that could greatly increase access to this type of medical intervention and give women suffering uterine infertility a viable option in bearing their own children. He adds that the first transplants from living donors were a medical feat, but that living donors are rare and the number of organ donors that agree to donate organs upon their death far outnumber these, thus offering a much larger donor population.

References

1. Dani Ejzenberg, Wellington Andraus, Luana Regina Baratelli Carelli Mendes, Liliana Ducatti, Alice Song, Ryan Tanigawa, Vinicius Rocha-Santos, Rubens Macedo Arantes, José Maria Soares, Paulo Cesar Serafini, Luciana Bertocco de Paiva Haddad, Rossana Pulcinelli Francisco, Luiz Augusto Carneiro D'Albuquerque, Edmund Chada Baracat. Livebirth after uterus transplantation from a deceased donor in a recipient with uterine infertility. The Lancet, 2018; DOI: 1016/S0140-6736(18)31766-5

2. Ledig S, Wieacker P. Clinical and genetic aspects of Mayer-Rokitansky-Küster-Hauser syndrome. Med Genet. 2018;30(1):3-11.

3. Luke B. Pregnancy and birth outcomes in couples with infertility with and without assisted reproductive technology: with an emphasis on US population-based studies. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017;217(3):270-281. DOI: 1016/j.ajog.2017.03.012

4. Infertility definitions and terminology. World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/topics/infertility/definitions/en/. Published 2018. Accessed December 7, 2018.