Once such disease with deadly potential is measles (rubeola). Currently vaccination programmes are regarded as one of the most cost-effective public health interventions and has prevented between 2 and 3 million deaths every year. Diseases such as tetanus, diphtheria, whooping cough and measles are some which top the list requiring these health interventions in order to remain under firm control.

Why are measles infections such a concern?

This virus causing airborne disease is highly contagious, spreading from person-to-person. Once the virus is contracted, an infection affects the body’s respiratory system resulting in symptoms similar to those of flu (influenza) such as fever, nasal congestion, red eyes and a rash of tiny red spots. The virus lives in mucus in the body, making it easily transmittable through a simple cough or sneeze.

The virus can also live for up to 2 hours outside of the human body, making touched surfaces exposed to someone with an infection easy targets for spreading the disease too. It is estimated that as many as 90% of individuals who come into contact with an infected individual are likely to contract the disease if they have never been vaccinated. Measles is considered much more contagious than influenza (flu), chickenpox or even polio. If severe, an infection can lead to complications such as pneumonia or encephalitis, both of which can be fatal.

The fact that a vaccine has been developed and proven to be almost 100% effective is increasingly frustrating for medical professionals in particular, where coverage target drops are concerned.

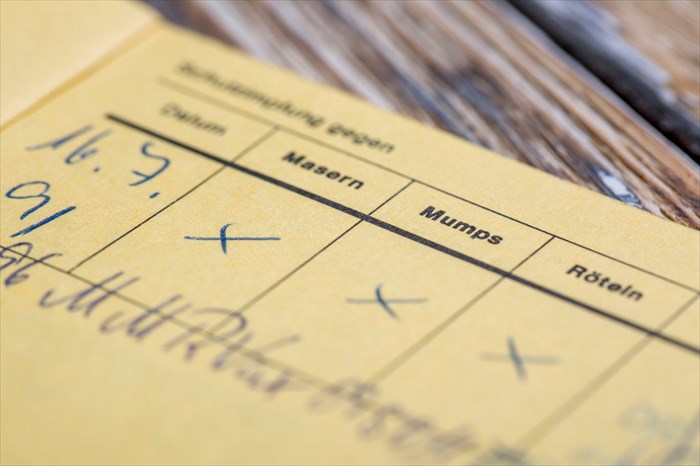

Measles is a preventable disease and all it takes is two doses of the MMR vaccine – one between and 12 and 15 months of life, and again between the ages of 4 and 6. Teens and adults can also check their immunity status and receive vaccinations should it be required as well. Two doses of the vaccine have been proven to be 97% effective. One dose has shown a success rate of 93%.

A very small percentage of individuals would need to skip these vaccinations for medical reasons, such as those with compromised immune systems and associated health conditions, or severe allergies.

The MMR vaccine was introduced in 1963, and resulted in a 99% success rate in preventing cases of measles in countries across the world that adopted the immunisation programme (compared to the pre-vaccine period). As little as a few dozen and up to a few hundred cases per year were all that have been reported since then.

Measles in the spotlight across Europe

Outbreaks of measles has been making headlines frequently around the world of late. The small percentage decrease in coverage target for 2016 is raising concerns, and especially so as recent outbreaks in Europe have resulted in at least 35 fatalities this year so far. Medical professionals have seen many cases indicating that measles is spreading through Europe.

This has prompted the CDC (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention) to issue travel warnings to parents with unvaccinated children, urging immunisations before entering risk areas. The World Health Organisation (WHO) has labelled these deaths an “unacceptable tragedy,” since all could have been prevented with vaccinations.

Risk is creeping into danger zones around the world. An estimated 24 000 children in the United Kingdom are at risk of measles, mumps and rubella each year. To date measles has not been considered endemic in 37 European countries, but pockets of low vaccination coverage have shown an increase in the spread of diseases among populations that have chosen not to be immunised.

The number of fatalities in Romania (along with 8 246 reported measles cases since January this year), for instance has been attributed to a growing number of the country’s population choosing not to vaccinate. At least 80% of the population are, to date, vaccinated against measles, but a growing number of ‘anti-vaxxers’ is being encouraged by public figures and religious organisations. At least 180 000 children are not vaccinated in Romania. Another notable reason vaccinations have taken a dip is due to a lack of access to health services, which goes hand in hand with low income and poverty.

The country is also facing vaccine shortages and delays (currently there are only 500 000 vaccine doses available in the country until the end of 2017), which is also contributing to the problem.

A survey conducted recently in France found that as many as 3 out 10 now distrust the effectiveness of vaccines, and only 52% of the population feel that the benefits of immunisation programmes outweigh disease and health complication risks.

Vaccination coverage in Europe is now estimated at below 95%, especially in France, Germany, Italy, Romania, Poland, Ukraine and Switzerland.

The USA raises red flags in a new study

The most recent study into the effects of declining vaccination rates led by Dr Peter Hotez, who is the dean at Baylor’s National School of Tropical Medicine (Houston, Texas, USA), along with M.D. / Ph.D Nathan Lo (division of epidemiology at Stanford University’s School of Medicine). With anti-vaxxers on the increase, study authors wanted to assess the impact of small coverage reductions, which have been seen across the globe, measured against the number of measles cases reported.

The study has published an analysis which projects that as little as a 5% decline in MMR vaccine coverage could potentially triple the number of infections in children between the ages of 2 and 11. This warning alerts to consequences of a substantial nature for public health sectors and the economy of countries concerned. A further red flag alerts to consequences potentially reaching adolescents and adults who are not immune to the disease too.

The study focussed on all 50 states in the USA, as well as data collected by the CDC in 257 countries (of children aged between 2 and 11), and excluded cases with a medical (or other) vaccination exemption. Findings of the study were published in the journal JAMA Pediatrics on 24 July 2017.

Since the introduction of a vaccine, immunisation programmes adopted a safety threshold known as ‘herd immunity’. This means that a programme implementation requires that enough of an area’s population are immunised so as to maintain the safety of the remainder. This is why the global vaccination coverage target is set to between 90% and 95% in order to prevent outbreaks.

Since 1998, this safety threshold came under fire, and even more so since a comprehensive review in 2014 released data contradicting a rising concern about the link between the vaccine and the development of autism. To date, the vaccine as a cause of this condition has not been conclusively proven. This coupled with religious objections to vaccinations are thought to be contributing to growing numbers of recent outbreaks.

The study acknowledged American outbreaks that affected 383 Amish community members in Ohio, USA in 2014, and an outbreak of 159 cases that originated in Disneyland, California in 2015 (where a previous study found that vaccination coverage was only at 70% instead of the required 90%), and another affecting 79 Minnesota community members (children of Somali descent born in the USA) earlier this year (2017).

Study findings do not appear to be all that surprising, but are certainly concerning. Small declines are already affecting the safety threshold of countries, reducing the ‘herd immunity’ effect. Outbreaks are becoming more frequent and larger, and countries around the world are increasingly becoming dotted with ‘hot-spots’ where widespread outbreaks are a real possibility (due to lower immunity coverage rates). The danger is that population immunity may already be shifting from being highly vaccinated (reducing exposure) to being increasingly unvaccinated.

Currently the coverage vaccination target in the USA stands at 93% (immunised children between the ages of 2 and 11 years). The projection warns that a drop to 88% could potentially result in at least 150 more annual cases of measles, costing the country at least $2.1 million.

The study also notes that only vaccination and infection data from children aged between 2 and 11 were analysed. If the most recent study had to have included cases of infants, adolescents and adults, the authors feel that associated costs would be considerably higher. Increasing exposure for infants is another major concern, since young babies cannot be vaccinated.

Is non-negotiable legislation the answer?

Some successes have been made where immunisation programmes have been effectively implemented. In June this year, talk of infections was not all gloom when WHO announced that two of the 11 South-East Asian countries (the Maldives and Bhutan) that were given a vaccination deadline are now measles-free areas.

Such successes, some may argue, have had to be urged along and strongly by both governments and health organisations. With European governments taking a firm stance on vaccination programmes in recent weeks, it may be that mandatory vaccinations just might be one of the best ways to ensure that small declines in coverage targets don’t have such detrimental effects on global populations. And with the ease at which people can travel from place to place, virus transmission is all too easy. The most recent study makes the concern very clear – it doesn’t take all that much of a decline to cause a worrying re-emergence of this potentially fatal infection.

But, not all countries are in a position to ‘enforce’ mandatory vaccinations, as in the case of Romania (and many, many others). While some countries have a little access to vaccines, others have little to none. Health organisations are doing all they can to provide as much access as possible.

There are many middle-income populations living in areas lagging behind in acquiring and administering some of the newer (and more expensive) vaccines. External support is difficult to come by and health budgets are simply not enough to procure the much-needed vaccines. UNICEF (The United Nations Children's Fund) have worked hard (through studies) to emphasise the importance of investing in countries that are most poor or marginalised, and prioritising the need to ensure immunisation programmes can be implemented. When it comes to a means that can save lives, making these programmes a priority is key.

A lack of sufficient access is one challenge, the other is the growing number of anti-vaxxers, which medical professionals continue to request seek out more accurate information regarding vaccination safety. Vaccination education is becoming more and more critical among populations the world over.

When more than half of the world’s populations reside in urban areas, including poorer settlements or slums, risk of infection outbreaks is high. Groupings in such numbers shouldn’t be unvaccinated or even under-vaccinated either.

Many in the medical industry hope that education will reach a wider range of ears faster than the virus can cause further harm. No one in the field really wants to see the virus become ‘the voice’ that speaks the loudest, after many more outbreaks have occurred and higher numbers of fatalities are recorded. To date, every major health organisation has rejected the claim that vaccines and autistic conditions are linked.

As things stand now, globally, 85% (a little below the minimum safety threshold requirement) of children are given their first dose of the measles vaccine before their first birthday. This percentage drops to 64% receiving second doses, which effectively leaves a window wide open for pockets of outbreaks – as has already been seen around the world.

The study’s findings reiterate that in order for the world’s populations to be safe from measles, we must find ways to regain the safety threshold. Those in the medical field can’t stress enough how much this should be non-negotiable. Perhaps then, stringent measures such as mandatory laws, like France has recently stipulated, will help to protect current and future populations from the debilitating effects of measles.