Diagnosing and treating sickle cell disease

How is sickle cell disease diagnosed?

Often, acute pain is a red flag and is commonly felt in the hands and feet. Other symptoms which will show signs include anaemia, respiratory infections, ulcers, heart problems and issues with delayed growth. If any of the aforementioned symptoms are mentioned to a doctor during an initial consultation, he or she is likely to recommend testing for SCD.

Once your doctor (general practitioner or paediatrician) feels they have a detailed enough medical history and a sufficient understanding of a patient’s symptoms, the following screening tests may be recommended:

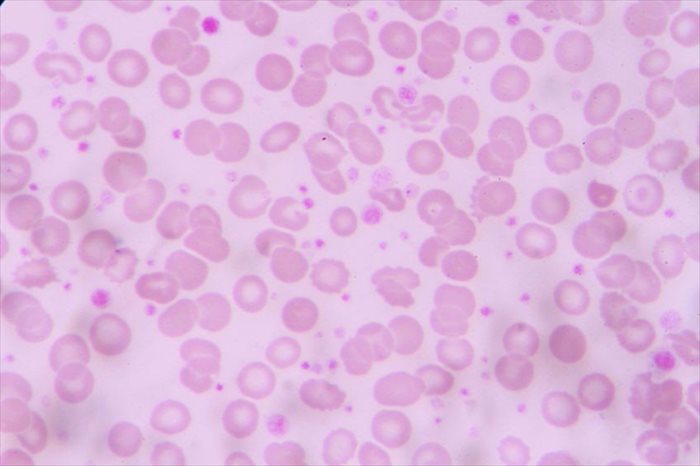

- Blood tests: A doctor will check a patient’s blood count to assess whether there is an abnormal Hb level. Blood films will also show any irregularities with RBCs. A sickle solubility test using a blood sample will check for the presence of Hb S (haemoglobin S).

- Hb electrophoresis: This test is typically used to conclusively diagnose SCD by measuring all of the blood’s haemoglobin types.

If screening tests show the sickle cell gene, additional tests may be recommended to assess any obvious complications of the disease. This will also depend of what was discussed during the initial consultation.

Sometimes, prenatal testing can be done to check for the sickle cell gene in the amniotic fluid or placenta of a pregnant woman before a baby is born. This is highly recommended if one or both parents is aware that they have the disease or may be a sickle cell trait carrier. Genetic counselling is also advisable where the risk of passing on the gene is high or probable.

Prenatal testing involves:

- Amniocentesis: Amniotic fluid cells will be examined for the sickle cell gene. A needle is inserted through a woman’s belly and into her uterus, usually between weeks 15 and 20 of pregnancy. A sample of fluid is retrieved for analysis.

- Chorionic villus sampling (CVS): This test is performed at 10 to 12 weeks during pregnancy, making results available sooner than with an amniocentesis test. A sample of chorionic villus cells (tiny, finger-shaped growths situated in the placenta) are collected via a catheter (thin tube) inserted into a woman’s vagina. Samples can also be taken through a long needle inserted into a woman’s belly, using an ultrasound as a guide for locating the correct spot for retrieval.

Treatment procedures

Currently, there is no way to effectively cure SCD. Symptoms will need to be routinely monitored and treated as and when health complications arise. Tests will also become routine during a person’s lifetime. A medical professional will help to alleviate symptoms as best, ensuring that serious complications are avoided in any way possible.

For the parents of a child with SCD, a diagnosis will mark the beginning of a lifelong learning process for both you and your little one. Your doctor will want to work closely with you to help you recognise symptoms as they occur, how to go about caring for your child as they grow, as well as what to do in the event of a more serious concern requiring emergency intervention.

The treatment plan for children may involve:

- Routine vaccinations throughout childhood

- Penicillin antibiotics (to be taken daily between the ages of 2 months and 5 years when young children are at most risk of infection).

- Medications (hydroxyurea) that assist with changing the shape of RBCs and preventing sickle cell crisis, as well as reducing the need for blood transfusions and hospitalisations.

- Multivitamins (especially those with added iron which may be needed during infancy) and folic acid supplements.

- Protein supplements may also be needed to assist with gaining sufficient weight.

- Transcranial doppler ultrasounds will be recommended on a routine basis from the age of 2. The screening will examine blood flow in the arteries of the head and neck. This test is useful for assessing the risk of stroke. If chances are high, a child may be given a blood transfusion to try and prevent this.

Routine tests a person will experience well into adulthood also include:

- CBC (complete blood count) tests

- Urine tests

- Organ function and vision function tests

- Hepatitis C tests (especially if a person receives frequent blood transfusions)

Pain management

This will, unfortunately, be a chronic ailment for those living with SCD. A doctor or pain treatment specialist (physical therapist, chiropractor, rheumatologist, orthopaedic surgeon, acupuncturist, or osteopathic doctors) can help to alleviate any level of discomfort, as well as assist you with developing pain management skills.

A person with SCD will frequently experience painful crisis episodes and quite suddenly too (without too much warning). Pain also comes and goes unpredictably, and if not treated correctly can, in severe cases, become life-threatening. Pain is often difficult to treat in a SCD patient and frequently makes a person exhausted. It can be just as exhausting for a caregiver trying help alleviate pain and discomfort.

Dealing with chronic pain is challenging, but it can be effectively managed. Work closely with your health care providers and pain treatment specialists so that you can best target areas of the body taking severe strain sufficiently.

Men and young boys may struggle with priapism. This can also be quite painful, and as such should be assessed by a medical doctor for treatment. Likely treatment may involve oxygenation, hydration (plenty of fluids), a blood transfusion (if necessary), the administration of intravenous pain medication and possibly an assessment with a urologist.

Other necessary treatments for SCD may involve:

- Frequent red blood cell transfusions (improves the blood flow function of carrying oxygen and nutrients and increases the number of RBCs in circulation in the body). Packed red cells are removed from blood that is donated and then given intravenously to a person with SCD. A person does run the risk of increased infections and excess iron build-up with frequent transfusions – this can be damaging for organs in the body and as such should be closely monitored on a regular basis.

- Rehydration (intravenous fluids help to prevent dehydration which can cause RBCs to deform / ‘sickle’).

- Supplemental oxygen (administered via a mask) to improve breathing difficulties and increase oxygen levels in the blood.

- Pain medications may also be prescribed for crisis episodes. In severe cases, morphine may be necessary.

- Treatment for infections (medications may include penicillin antibiotics throughout adulthood).

- Vaccinations to prevent infections (particularly the flu shot or pneumococcal vaccine).

- A stem cell transplant or bone marrow transplant (children under the age of 16). A match donor is somewhat difficult to find and is usually a sibling. Where a match donor is not available stem cells taken from umbilical cord blood may be used for the transplant procedure. If a donor is available an SCD patient will need to undergo chemotherapy or radiation to reduce or kill off bone marrow stem cells. The healthy donor cells will then be intravenously injected into the bloodstream, allowing them to travel (migrate) to the bone marrow. The transplant aims to stimulate the production of new red blood cells. It is a risky procedure and requires a long stay in hospital. A patient will be monitored carefully following the procedure as the body may reject the newly transplanted stem cells. If this happens, it can be life-threatening.

- Surgeries to correct complications which arise may be necessary (for instance, removing the spleen or repairing problems with the eyes).

What is the outlook for someone with sickle cell disease?

Once diagnosed, there is no way back. As a genetically inherited blood disorder, sickle cell disease is not a condition that can be prevented. The earlier it is diagnosed within the months following birth, or foreseen through prenatal testing, the better it can be managed.

If not sufficiently treated and severe complications occur as a result of crisis situations, it can happen that infants and young children lose their lives far too soon. Young children are at high risk of infections at this age and it can be fairly dangerous if they do contract something.

With sufficient and careful treatment, life expectancy is relatively good and an optimal quality of life can be achieved well into middle age (and beyond).