What is smallpox?

Defining smallpox

A contagious infection, smallpox has a somewhat devastating history. It could be easily spread once contracted, with progressive symptoms (that were often disfiguring) and high mortality rates. At least a third of infections in unvaccinated individuals before 1980 resulted in deaths from the disease. (1)

Characteristics of the disease include a very high fever and fatigue, soon followed by a distinctive body rash, mostly affecting the facial area and limbs (arms and legs). The spotty rash then develops into fluid-filled lesions (pustules) which form a crust. These crusted formations dry out, forming scabs and fall off the surface of the skin, leaving behind disfiguring scars.

It is possible for an infection to be successfully treated, but not without some permanent scarring. In some instances, a person can even become blind as a result of infection.

For now, the condition is considered to be eradicated, due to the successful implementation of vaccination for prevention purposes. There have been no known infections since 1977 (i.e. medically reported cases of the virus occurring naturally). That said, there is growing concern that the virus causing the disease (i.e. the variola virus) could be ‘re-created’ in the laboratory environment, and thus pose a threat to the world population once again. Small, authorised quantities of the variola virus are stored in two separate World Health Organisation (WHO) research laboratories in Koltsovo, Russia (State Research Centre of Virology and Biotechnology) and Atlanta, Georgia, USA (at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention / CDC). These authorised samples are kept for research purposes only. (2)

Long feared as a possibility, smallpox has been labelled a ‘category A bioterrorism agent’ which can be used as a ‘weaponised virus’. What this ‘category A’ classification means is that the pathogen (viral organism) responsible for the disease is capable of posing a high risk to countries and their populations. An outbreak could cause a spike in mortality rates and result in mass disruption to health sectors.

Smallpox is not considered an immediate health threat, but preparations for epidemic re-emergence have been issued by the CDC (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention) to governments around the world to take note of so as to better handle situations should a biological attack occur.(3) Scientific research is also ongoing so as to ensure that in the event of a re-emergence, countries are sufficiently equipped with the most up to date vaccines and pharmacological treatment methods to stop infection in its tracks and prevent severe complications.

A brief history of smallpox and the virus that causes it

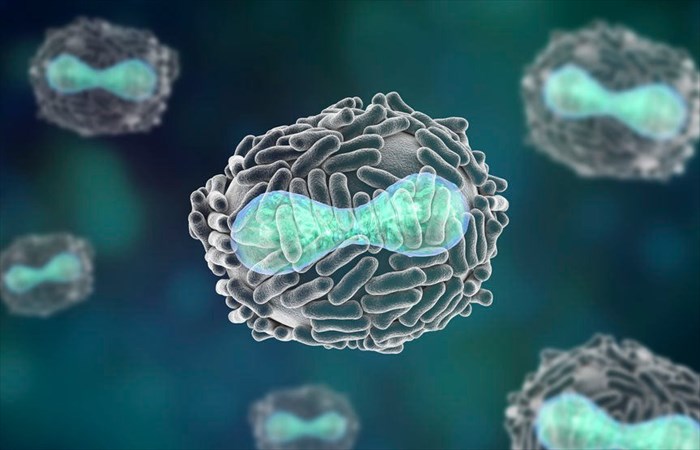

The variola virus (VARV) is responsible for the development of this highly infectious disease. This virus is a member of the genus Orthopoxvirus – a group of viruses (belonging to the Poxviridae family), which are also associated with the monkeypox virus (MPXV), vaccinia virus (VACV), camelpox virus (CMLV) and cowpox virus (CPXV) – all infectious diseases which are transmittable from human to human or from animal to human.

Poxyviridae viruses are characterised as linear (or brick-shaped), double-stranded DNA (deoxyribonucleic acid) viruses which are able to replicate themselves in living cells (i.e. host cells).

There are two sub-families of this virus form:

- Chordopoxvirinae (capable of infecting vertebrates / animals)

- Entomopoxvirinae (capable of infecting insects)

VARV resulting in smallpox infections does not appear to occur in a carrier state but is known to be most stable at low temperatures and humidity levels.

Smallpox is transmittable between humans only, causing large-scale epidemics for many years prior to the implementation of an effective vaccination. It is said to have resulted in more than 400 000 annual European deaths during the 18th Century. (4)

The origins of VARV have been reasonably well researched over the years so as to gain a clearer understanding of the mechanistic patterns of the virus, and how it came to have such a dramatic impact on the wellbeing of populations around the world. Its precise origins are, however, not entirely known but some ancient data and research has turned up some interesting clues. VARV has been associated with an African rodent and camels but is yet to be distinctively linked to these animals.

It is also thought that early infections may have originated in ancient Egypt (around the 3rd century BCE), spreading through the development of international trade between the 4th and 15th centuries (with some written descriptions speculating that the disease was rife in China, Korea and Japan).

Other speculations have mentioned possible occurrences in India around the 7th century and in Asia Minor (the westernmost protrusion of Asia) during the 10th century. The disease could have reached the Western world via European explorers by the early 16th century (being carried from one location to another during the Crusades, Portuguese occupation in parts of Western Africa, European colonisations and the African slave trade etc.), causing waves of illness. It is believed that the growth of civilisations and trade route expansions most likely resulted in the widespread transmission of the disease. By the 17th and 18th centuries, European colonisations and British explorations could have introduced the disease to North America and Australia.

Are there different types of smallpox?

There are two primary variants of VARV (smallpox types):

1. Major:

VARV major (or variola major) is the predominant epidemic viral strain that resulted in mass infections all over the world, including Europe, Asia and Africa until the 20th century. Mortality rates were as high as 30% to 50%.

There are 5 subtypes of VARV major:

- Ordinary smallpox: The most common form of the disease, this subtype occurs in at least 90% of all reported cases.

- Modified smallpox: This subtype is a milder form of the disease which can occur in individuals who have been vaccinated against the disease.

- Malignant / flat smallpox: This subtype is a severe form whereby skin lesions / bumps develop beneath the skin’s surface (and do not project on the surface of the skin as is most characteristic of the disease).

- Haemorrhagic / fulminant smallpox: This subtype is considered highly severe and rare. Lesion haemorrhages in the skin and mucous membranes can result in life-threatening conditions.

- Variola sine eruptione (variola sine exanthemata): A less common form of the disease, wherein symptoms that occur are not accompanied by the characteristic rash. Some individuals may be asymptomatic or experience short-lived symptoms such as a headache, fever and other flu-like ailments. This form may also affect previously vaccinated individuals.

2. Minor:

VARV minor (or variola minor) is the strain that was endemic to certain European, American (North and South), Australian and African (South Africa) countries since the second half of the 20th century. Mortality rates were far lower (around 1%).

Other known forms of smallpox included:

- Pharyngeal form of smallpox: This form can occur in vaccinated individuals, resulting in a spotty rash in mucous membranes – mainly affecting the soft palate (soft tissue at the back of the roof of the mouth), uvula (fleshy tissue which hangs at the back of the mouth over the tongue) and pharynx (cavity behind the nose and the mouth). It is typically mild and can be effectively treated.

- Influenza-like form of smallpox: In this mild form of the disease a skin rash rarely occurs. This form is also more typical in individuals who have received sufficient vaccinations against the condition.

- Pulmonary form of smallpox: Characteristic smallpox symptoms of this variety are typically severe and include cyanosis (a condition which causes the skin and / or mucous membranes to become discoloured, appearing blue or purple due to low oxygen levels in the red blood cells or a lack of oxygen circulation in the body). This form of the disease may affect individuals who have very little or no immunity against smallpox at all.

Is smallpox contagious?

Smallpox was highly contagious and could be spread from person to person via close personal contact. To date, research has not identified a transmission route between insects / animals and humans. Air in enclosed environments is also not considered a primary transmission route.

There was a general incubation period of between 7 and 17 days once a person had been exposed to the infectious agent. (5) Once a fever developed, an infected person became contagious and could transmit the virus to another person.

A person was considered to be at their most contagious when lesions and bumps first developed around the mouth and throat areas (normally within the first week). From there, the virus was mostly transmittable through contact with the moisture droplets released during respiration by an infected person – most commonly from the nose (when sneezing) or mouth (during coughing or through saliva). Transmission contact with infected moisture droplets quickly led to the infection of another person via the mucous membranes of the respiratory tract.

Lesions and bumps which formed on the skin contained fluid (either clear, opaque or pus) and the variola virus. Contact with this fluid and the scabs which later formed could also spread infection (although to a lesser extent than the respiratory secretion and saliva contact route). Thus, contaminated materials and objects (i.e. that had contact with infected lesions, bumps and scabs), like clothing and bed linens (referred to as fomite transmission), could also contribute to the spread of infection to other individuals.

An infected individual remained contagious until the very last scab had fallen away from the body.

Transmission of the disease as a result of the smallpox vaccine which uses the vaccinia virus (a live virus belonging to the same family) in order to achieve immunity was also reported as being possible. Such cases have shown that sexual transmission of vaccinia was also possible if an unvaccinated partner came into contact with another who had been recently immunised (i.e. secondary vaccinia which can be transmitted to other partners as well).

The natural smallpox virus (variola) was transmittable via respiratory secretions. In contrast, the vaccinia virus which is used in smallpox vaccines, showed the potential for transmission via direct contact through mucosal membranes or broken skin before the healing of the inoculation site was completed. Genital lesions could occur, along with other symptoms of the disease. If encountered by medical professionals, a distinction between smallpox and a possible genital herpes infection (herpes simplex virus type 2 / HSV-2) had to be made.

References:

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. June 2016. What is Smallpox?: https://www.cdc.gov/smallpox/about/index.html [Accessed 06.04.2018]

2. National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. December 2014. Smallpox: https://www.niaid.nih.gov/diseases-conditions/smallpox [Accessed 06.04.2018]

3. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. December 2016. Bioterrorism: https://www.cdc.gov/smallpox/bioterrorism/public/index.html [Accessed 06.04.2018]

4. US National Library of Medicine - National Institute of Health. March 2015. The Origin of the Variola Virus: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4379562/ [Accessed 06.04.2018]

5. World Health Organization. June 2016. Frequently asked questions and answers on smallpox: http://www.who.int/csr/disease/smallpox/faq/en/ [Accessed 06.04.2018]

Other Articles of Interest

Mumps

Mumps can be a painful condition that results in the swelling of the face. The diseases dissected...

Diarrhoea

Suffering from a runny tummy? Having diarrhoea can often be an embarrassing and even painful experience. Find out all you need to know about dealing with and combating this condition.

Molluscum Contagiosum

Molluscum Contagiosum is a highly contagious virus that affects your skin in the form of raised bumps or lesions. Find out more about this virus here...