Defining liver cirrhosis

What is cirrhosis of the liver?

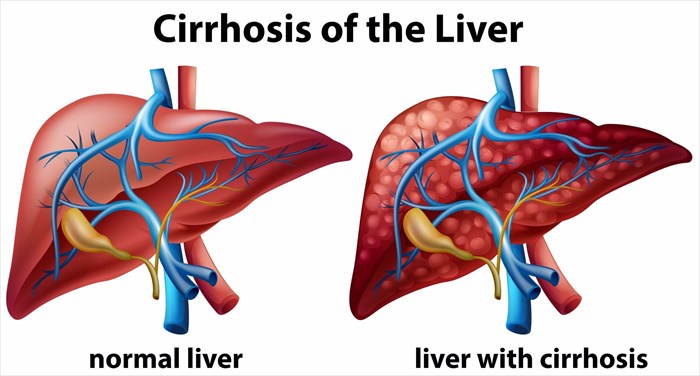

The late stages of liver fibrosis (severe scarring due to the accumulation of an abnormally large amount of scar tissue on the liver) or chronic liver disease is known as cirrhosis. At this stage, extensive damage results in poor function of the liver due to long-term exposure to toxic causes, such as excessive alcohol consumption (which is chronic) or infections (specifically hepatitis B and C). Damage to the liver prevents it from performing its normal functions, one of these is to effectively detoxify the body of harmful substances, allowing vital nutrients to circulate and cleaning out the blood.

Scarring occurs as a result of injury and damage inflicted on the organ. Injury may occur as a ‘single event’ (new or short-term acute cause) such as the contraction of an infection (like hepatitis) or chronically (i.e. repetitive damage over the course of months or years), such as chronic infections or daily alcoholism.

With each injury occurrence (including infection and disease), the liver responds by trying to repair itself, resulting in the build-up of strands of scar tissue. Cells in the liver respond to damage by becoming inflamed, some dying off and forming scarred tissue. Those cells that do not ‘die off’ multiply as a way of attempting to regenerate the organ, forming regenerative nodules (clusters of newly-formed liver cells). The liver hardens and becomes lumpy as nodules of cells develop and accumulate. Inflammation in the liver causes the organ to swell, which can later shrink and increasing damage hinders the organ’s required function.

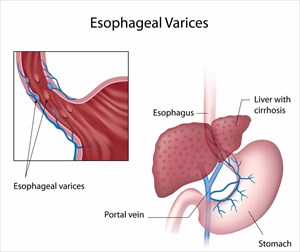

The repetitive cycle of damage, which can take many years to develop, ultimately makes it increasingly difficult for the liver to function as it should, and thus has negative effects on the remainder of the body. It becomes increasingly difficult for blood to travel through the portal vein (a large vein which normally allows blood flow into the liver), and blood can then accumulate or leak into the spleen with the building pressure. The more damage occurs, the higher the risk of developing complications, known as decompensated cirrhosis, which can be life-threatening.

Once damaged, scarring of the liver cannot be reversed. The more the liver is unable to function normally, the higher the risk of total liver failure (the final stage of liver disease). An early diagnosis is the best possible scenario whereby the underlying cause of cirrhosis may be effectively treated, preventing further damage.

As yet, there is no effective cure for cirrhosis, but there has been some recorded success with liver transplants. Treatment options should be focused on alleviating symptoms of an underlying cause and thereby slowing down the scarring cycle, preventing further irreversible damage.

Cirrhosis and the liver

The largest organ in the body, the liver is one of the most crucial. Located on the upper right side of the body (abdomen), just beneath the diaphragm and lower rib cage, the liver is responsible for producing substances that fend off infections when they occur, assisting with blood clotting, filtering toxins or other infectious agents, such as bacteria, from the blood (thus purifying the blood), as well as assisting with storing energy (sugar and vitamins) and the digestion of nutrients consumed (through the production of bile which assists with the absorption of fats, vitamins A, D, E and K, and cholesterol).

- Protein synthesis: Proteins produced by hepatocytes for blood clotting and those needed for albumin, which maintains fluid within the body’s circulatory system.

- Manufacturing of cholesterol and triglycerides: The liver breaks down glucose and turns the substance into glycogen. This is then stored in the liver, as well as in all the muscle cells (energy storage).

- Detoxification: A by-product of metabolism, ammonia, is converted into urea in order to be removed from the body (with the aid of the kidneys) through urine. Other substances, such as medications and alcohol are also broken down by the liver.

- Storage of chemicals: Folic acid, vitamin B12, vitamin A (to assist with vision), vitamin D (to assist with absorption of calcium), vitamin K (to assist with blood clotting) and iron (to assist with regeneration of red blood cells).

In order to maintain these essential processes in the body, liver cells are required to function normally and the organ must be able to function seamlessly with the body’s blood flow. All substances in the body which are added or removed by the liver are also transferred to and from the organ in the bloodstream. A hiccup in this system can result in the deterioration of critical functions. When inflamed or enlarged, the liver increases in size across the upper abdomen and also towards the navel area (umbilicus).

What happens when it all begins to go wrong?

A rich supply of blood is needed by the liver and is obtained via two fundamental sources, the hepatic portal vein which transports deoxygenated blood and nutrients, and the hepatic artery which carries oxygenated blood. This effectively divides the liver into two lobes (sections).

There are thus two critical relationship functions that contribute to the development of cirrhosis – the relationship between the liver and blood, and the relationship between the liver and the channels through which bile travels.

Blood and the liver: Only a small amount of blood is actually supplied to the liver by the body’s arteries. Most of the supply is delivered through intestinal veins (i.e. those in the gastrointestinal tract – intestine, stomach and colon) and spleen before being circulated to the heart. The hepatic portal vein is the main channel of transference which passes through the liver from the intestines and then breaks into numerous smaller veins. These smaller veins are known as sinusoids and are able to come into close contact with the cells of the organ (i.e. liver cells are able to 'line-up' along the length of these tiny veins). Blood that is supplied to the liver cells, passing through the tiny sinusoids, collects in veins which increasingly become larger, forming the hepatic vein (a single vein), and ultimately delivering blood to the heart via the inferior vena cava (the vein transporting blood to the heart from the liver).

Cirrhosis obstructs the blood flow process through the hepatic portal vein (causing a back-up of blood known as portal hypertension), and the cells of the liver, thus damaging the organ’s ability to add or remove (purify) substances from the blood. Obstruction causes an increase in pressure in the portal vein, which forces blood to 'seek other avenues' (veins which bypass the liver altogether) in order to return back to the heart. Contact between the liver and blood is thus lost, and liver cells are reduced in the malfunction, resulting in the manifestations of cirrhosis. Portal hypertension can lead to further damage, such as oesophageal varices (abnormal and enlarged veins in the oesophagus) which may rupture and bleed.- The liver and bile: The relationship between the liver and the channels through which bile (which is produced by liver cells) flows is also compromised. Bile is essential for the digestion of vital nutrients and removing toxic substances from the body. Normally, bile is secreted from the liver into small channels (canaliculi) which line the sinusoids and is then stored in a tiny sac under the liver called the gallbladder. The fluid is then emptied into tiny ducts which ultimately join larger ones (known as the biliary tree or system of tubes). These combine into one large duct that then enters the small intestine. From there, bile that enters the small intestine aids in digestion, and toxic substances are separated to be removed from the body through the stools (faeces). A malfunction in this relationship means that damage hinders the process causing abnormalities in the canaliculi (leading to a back-up of bile). The result is that toxic substances accumulate in the body and cannot be effectively removed, and digestion processes also become somewhat ineffective.

Other Articles of Interest

Liver Disease / Hepatic Disease

The liver is a phenomenal organ with the ability to heal itself. However, in some cases, the constant damage and abuse to it can cause liver disease and even liver failure.

Haemorrhoids / Hemorrhoids (Piles)

Commonly referred to as piles, haemorrhoids (also spelled hemorrhoids) is an uncomfortable, often painful swelling of veins in the anus and lower rectum. Learn more here ...

Ultrasound scan

What is an ultrasound scan and how does it work? We look at the numerous ways this screening and monitoring tool is used in medicine today. Here's everything you need to know...

Blood and the liver: Only a small amount of blood is actually supplied to the liver by the body’s arteries. Most of the supply is delivered through intestinal veins (i.e. those in the gastrointestinal tract – intestine, stomach and colon) and spleen before being circulated to the heart. The hepatic portal vein is the main channel of transference which passes through the liver from the intestines and then breaks into numerous smaller veins. These smaller veins are known as sinusoids and are able to come into close contact with the cells of the organ (i.e. liver cells are able to 'line-up' along the length of these tiny veins). Blood that is supplied to the liver cells, passing through the tiny sinusoids, collects in veins which increasingly become larger, forming the hepatic vein (a single vein), and ultimately delivering blood to the heart via the inferior vena cava (the vein transporting blood to the heart from the liver).

Blood and the liver: Only a small amount of blood is actually supplied to the liver by the body’s arteries. Most of the supply is delivered through intestinal veins (i.e. those in the gastrointestinal tract – intestine, stomach and colon) and spleen before being circulated to the heart. The hepatic portal vein is the main channel of transference which passes through the liver from the intestines and then breaks into numerous smaller veins. These smaller veins are known as sinusoids and are able to come into close contact with the cells of the organ (i.e. liver cells are able to 'line-up' along the length of these tiny veins). Blood that is supplied to the liver cells, passing through the tiny sinusoids, collects in veins which increasingly become larger, forming the hepatic vein (a single vein), and ultimately delivering blood to the heart via the inferior vena cava (the vein transporting blood to the heart from the liver).